Mulally’s adherence to not just the principles of Kai, but also to the equally important principles of Zen, has enabled Ford employees’ curiosity and creativity to begin an upward trend of sustainable personal and professional improvement.

Mulally’s own penchant for improvement occurred at the same time in history when other leaders in America’s automotive industry were putting their corporate hands out.

Yet Mulally was willing to bet the entire Ford franchise-Blue Oval and all-nearly twenty-five billion dollars worth-that Kai and Zen together would go farther than any government assistance, as he set forth on his journey to improve Ford’s ailing system.

But even the mid-west Kansan Mulally knew, Kai without the Zen, was like pie a’la mode without the a’la mode; a New York bagel without the cream cheese, or an eight-cylinder engine that was firing on just five.

If he could just somehow put Kai and Zen together, he knew he could create a new and distinct possibility.

That is, an ever-improving culture, and a better process for leaders and employees to collaborate among one another to solve problems and then begin making sustainable improvements.

For Mulally it was clear: Kai and Zen together had the potential to put Ford’s culture into high gear with employee engines producing maximum torque and efficiency even when having to occasionally run at marginally slower speeds.

Mulally also saw his employee’s curiosity and creativity-both previously in the rumble seat from lack of use and continuous disengagement, could bring back the lustre to the once shiny Blue Oval and perhaps even to the rest of America.

Putting two of man’s most important traits both back into the front seat could allow Ford employees to produce higher-quality cars faster, so people would want to return to dealer’s showrooms more often.

Leaders would also benefit from the restoration of their employee’s perpetual, but previously bridled yearning for learning.

And at Ford, Kai and Zen might just become the new Leadership toolbox to pull from to continuously improve people; the methods people used to produce goods and services; the machinery that assisted them in the process, and the materials they used in producing them.

But enough about Kai and it’s close cousin Zen.

Let’s look at how Mulally finally married them together-much in the same way the Japanese originally intended them to be.

Let the transformation begin-how Mulally did it

Rather than looking at employees as the primary causes of loss behind poor productivity, Mulally took the paradoxical approach that loss is not driven by man’s poor work habits.

Loss is instead, driven by variation.

Unlike the traditional American car manufacturer’s leadership approach to “improvement,” leaders at the “New Ford” would continually seek to drive variation out of the system, rather than driving employees out of the variation through layoffs and other perpetual corporate attrition projects.

Ford’s new drive train

And this new leadership engine and employee transmission at Ford-one where the engine and transmission meshed together precisely to produce maximum cultural efficiency and sustainable horsepower, would consist of five new parts.

All integral components to making the Ford system function most effectively.

Respect.

Collaborative leadership.

Employee learning programs that benefited both the corporation and the employee.

Encouragement for employees to seek out and gain new knowledge.

Nurturing one’s own intrinsic motivation so he could do well for himself, therefore enabling others to do well for themselves.

Today, these are the five parts to Ford’s new drive–train.

Mulally added them, and then proceeded to teach everyone to collaboratively focus on how to use these tools to find the causes behind variation that was causing losses to rack up at Ford.

Driving variation out by hitting the bullseye rather than just the target

Mulally visualized variation as an arrow traveling through the air.

While heading directly towards the center of Ford’s bulls-eye, the arrow would often veer off course.

While the arrow would hit the target, it was not the precise center of the bulls-eye. Mulally knew, in any business an arrow rarely hits the bulls-eye.

But unlike other leaders, Mulally saw costs coming from causes, not costs as causes.

Therefore, the causes of the variation, not the archer/employee, was behind what was driving Ford’s arrow away from hitting its intended bulls-eye.

Ford’s legacy culture

But many managers and leaders at Ford still assumed they knew precisely why the arrow traveled off course; it was the employees who were behind the causes.

It’s what leadership had learned, and trained to think.

For Mulally, this had become the go to arrow in the traditional Ford quiver in terms of how they drove people, profits, and productivity.

The culture dictating there was always time to turn the spindle rate up on production, plenty of time to then do things over, yet little time for engaging workers in figuring out problems along with new, creative, and creative ways to sustainably improve the business.

Assuming why something has failed than knowing why it did, is expensive though.

Especially when, more often than not, the assumptions were wrong.

And that’s just the type of decision-making that had been very expensive and prevalent in Ford’s history, nearly bankrupting the company on more than one occasion.

Assuming the person-rather than the cause of the variation, was responsible for the economic loss, had largely become a Ford tradition.

Creating hope

But that is precisely why Kaizen offered Mulally, his employees, and America such great hope when he took over in 2006.

Under Mulally’s guidance, leaders and employees could collaboratively take steps to continuously investigate and understand the causes of variation and why the arrow was not hitting the center of the bulls-eye.

And Mulally had really good historical evidence-both human and otherwise, from which to draw from when explaining to his teams why trying to hit the center of the bulls-eye using employee input and perpetual feedback, mattered so much financially.

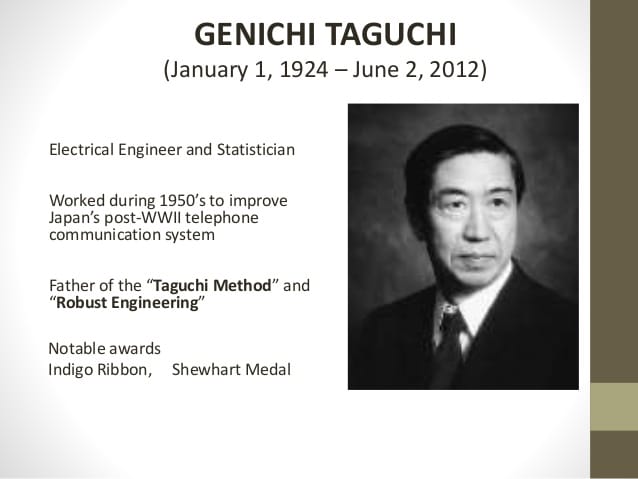

Dr. Genichi Taguchi and Dr. W. Edwards Deming-Japanese and American statisticians working together in Japan for nearly 30 years–both men whose ideas Toyota had pioneered their legendary approach to quality, cost reductions, and continuous improvement after, described the economics of variation similarly.

They described it like this.

The farther away an arrow arrives at the target away from the center of the bulls-eye, the greater the resulting financial loss will be to the business from the underlying cause(s) of the variation-even if the arrow arrives well within the customer’s specifications.

Ford found this out years ago when Mazda and Ford were both building transmissions for one of Ford’s product lines.

Transmissions built by Ford were failing, but Mazda transmissions-built to the same targets, were not.

When engineers found the causes behind Ford’s transmission failures, they discovered Mazda was building closer to the center of the bulls-eye – with employees continually trying to improve the proximity of the arrow to the nominal center of the bulls-eye.

Ford was content missing the bullseye, as long as they hit the target somewhere.

This decision had cost them millions in poor quality, customer rejects, and from the brand’s diminished value.

But it was not a linear type of financial loss-where the rate of loss remained constant as Ford progressed farther away from the bulls-eye.

It was an exponential loss where a graph of such a rate appeared not as a straight line, but as a curve that continually became steeper as the arrow proceeded away from the center of the bulls-eye.

Dr. Taguchi illustrated the example of his theory in the “Taguchi Loss Function.”

You’ll never see the cause behind why an arrow misses the bulls-eye called out on an income statement, but you’ll certainly see the financial loss spelled out.

It shows up as increased costs to the stakeholders, and decreased engagement of the employee’s minds and man’s creative nature.

Worse yet, employees experience more variation in their own lives when bosses announce they are “right-sizing” the company because the company can’t hit their own bulls-eye of their regular quarterly profit goals.

Alan Mulally and the employees at Ford changed course from this tradition.

They decided to pursue the multiple causes of variation.

Mulally, the greatest Kaizen leader, went back to finding out the real causes behind why arrows weren’t hitting the bulls-eye.

This helped employees consistently start tracking down Ford’s real disorder: the ongoing variation that continually drove losses up, and quality and productivity down.

Mulally used employee feedback to improve his aim on forever eliminating problems as they arose.

What made Mulally mnique

Kaizen leaders love failure-that is as long as they discover it quickly.

They recognize it as opportunity.

They set up a formal process that documents it, establishes the cause behind it, and set in motion actions to permanently remove its causes.

And just as costs go up exponentially the farther away the arrow lands from the center of the bulls-eye, costs go down exponentially the closer we move towards the nominal center of the bulls-eye.

That became Mulally’s new target and aim: understanding how to hit the center of the bulls-eye more often, not just aiming at the target itself.

Variation and loss is what gets eliminated by Kaizen leaders, not people’s minds and jobs.

Too many leaders are getting this entirely backwards; it is unnecessary, and devastating America’s most valuable asset: the contributions the human mind produces when freed from fear, and enabled by curiosity and creativity.

Why living our lives the way Mulally helped others live theirs, matters

Living our lives and running our businesses by understanding these improvement principles gives everyone working in a Kaizen environment their dignity and self-esteem back.

It simultaneously fosters greater teamwork, greater curiosity, and greater cooperation to find solutions to production related problems.

Nurturing these traits is the dream drive train that helps leaders improve their businesses faster than the dominant fear based leadership model now embraced within many executive suites.

Kaizen leaders like Mulally know that the underlying root causes of wasteful activities prevents employees from doing their jobs well.

These leaders know they hold the keys to improving productivity, and making life better for every American worker, and their families.

An ancient Buddhist proverb states:

To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the same key opens the gates of hell.

Knowing which gate to open, is the difficult choice leaders of today face in a rapidly expanding landscape of Kai and Zen opportunities.

Picking Kai or Zen alone will not drive innovation, nor will it drive employee engagement.

The two must marry to make sure the chosen gate to open, is the one that gets filled with perpetual opportunities for growth in employee and leadership development, much like Mulally proves is still humanly possible.