The history of the Digital Revolution and its consequences

Change alone is eternal, perpetual, immortal.” – Arthur Schopenhauer.

At the time of writing, these words seem to be more accurate than ever, as many different aspects of our world seem to be changing subtly or literally in front of our eyes.

Some of these changes are negative (e.g. climate change, deforestation, species extinction, resource depletion), but many of them are remarkably positive (e.g. rapid development of communication, the global rise of education and life expectancy, production automation, democratization).

However, there is no doubt that one of the primary sources of these changes, or at least a crucial element, is often a technological advancement.

It is not a surprise, from the wheel to the steam engine, technology frequently had more severe consequences than just purely “physical” ones.

Gutenberg’s printing press helped to mass-produce books leading to the rapid dissemination of information – but, also helped Martin Luther in igniting the Protestant Reformation.

The invention of the light bulb changed people’s sleeping patterns making it possible to work and be awake longer.

The washing machine improved women’s position in society by enabling them to enter the labor market.

More recently, social media played a significant role during the Arab Spring in 2011 by facilitating communication among participants of the political protests.

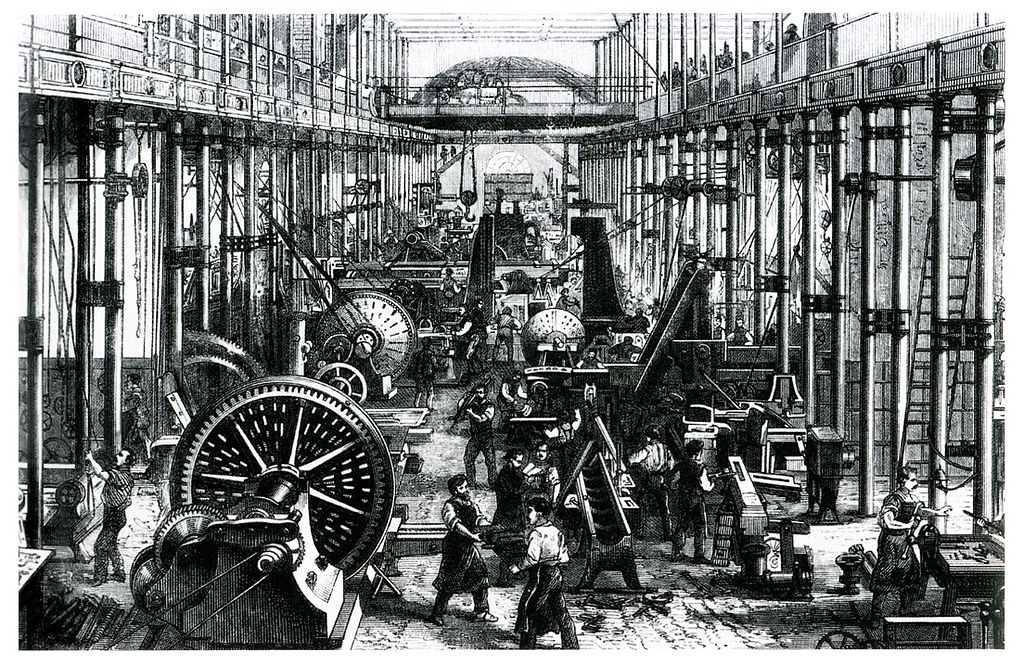

Revolutionary technological innovations of the last two centuries are often collectively grouped under the term “Industrial Revolution“.

The term was popularized by the English historian Arnold Toynbee (1852–83) who wanted to illustrate Great Britain’s rapid economic growth.

The First Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain in the 18th century and ended in approximately 1840.

During this period, primarily rural and agrarian societies in Europe and America transitioned into urban and industrial ones.

Thanks to the rapid development of technologies such as the steam engine, the steam locomotive, the Spinning Jenny and the introduction of the factory system, the idea of mass consumption was born.

Before, manufacturing got done using hand tools or primary machines. Because of these changes, the standard of living and GDP per capita began to increase steadily for the first time in history.

Some historians even suggest that the Industrial Revolution was an important event as the domestication of animals and the adoption of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution starting around 10,000 BC.

The Second Industrial Revolution spanning from approximately 1870 to 1914 resulted in innovations such as the popularization of electricity, the telegraph, the telephone, the airplane or the car.

Finally, The Third Industrial Revolution, also known as The Digital Revolution, initiated by the invention of the transistor in the 1940s and the microchip in the 1950s is still ongoing in the present day.

The core aspect of The Digital Revolution is the introduction of digital computing and electronics in place of mechanical and analog solutions supported by the following inventions of the Internet and mobile phones.

However, the Digital Revolution did not come out of thin air.

The origins of it can get traced as early as the 1640s when the French mathematician Blaise Pascal invented the first patented and commercially sold mechanical calculator made to help his father working as a tax supervisor.

Later in the century, the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz came with the idea of “Stepped reckoner” (ger. Lebendige Rechenbank) able to multiply and divide.

In the 19th century, the English mathematician Charles Babbage developed the construct of the “Difference Engine” to tabulate any polynomial function which later evolved into the “Analytical Engine” – a general-purpose computer able to execute different operations according to the given instructions.

Unfortunately, without funding from the British government of the time, Babbage’s ideas did not come to fruition during his lifetime, however, the Difference Engine was finally assembled in 1991 by a team at the Science Museum in London.

English mathematician Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace who was working on Babbage’s idea gets regarded as the first computer programmer – in her “Notes” she explored the potential of programming Babbage’s machine.

She is also thought to be the first to contemplate on the future of machines as the partners of humans and abstract concepts such as artificial intelligence.

Another giant step to the Digital Revolution was one of the first significant practical uses of punch cards (and electrical circuits to process information) by the US Census Bureau employee Herman Hollerith who automated with it the 1890 census that took one year instead of eight.

Hollerith’s company became a well-known International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in 1924. In 1931, an MIT engineering professor Vannevar Bush built the Differential Analyzer – the world’s first analog electrical-mechanical computer. However, it still was an analog device.

The major shift came in the 1930s when the British engineer Tommy Flowers invented the use of vacuum tubes in electronic circuits.

In 1937, the British mathematician Alan Turing created the foundation for theoretical computer science with the concept of Logical Computing Machine, which soon became known as a Turing machine.

In 1941, a German engineer Konrad Zuse developed the first fully working versatile programmable digital computer.

Other notable figures in computer science from this period include Claude Shannon, George Stibitz, Howard Aiken, and John Vincent Atanasoff.

All the previous research led to the invention of the first fully electronic, programmable, and operational computer known as Colossus in 1943, which was developed by the British to break the German wartime codes. However, it was not a general-purpose computer.

On the other hand, ENIAC (the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) designed mainly for differential equations needed for calculating missile trajectories could be programmed to challenge different tasks.

Completed by John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly and becoming fully operational in November 1945, ENIAC was more advanced than all the previous machines and is regarded as the first to have the full set of traits of a modern general-purpose computer.

Despite all the efforts, early computers were expensive and available only for universities, corporations and as it had usually been with revolutionary innovations – military.

It is reasonable to stipulate that the real Digital Revolution began in 1947 when the transistor got invented by American physicists John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley – later awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for their achievement.

This small device could amplify electric current and switch electronic signals while being smaller and requiring less power than vacuum tubes.

One of the first commercial products making use of this technology and defining the Digital Revolution was the Regency TR-1 radio launched by Texas Instruments in 1954. Within a year, 100,000 units got sold, becoming one of the bestselling new consumer products in history.

Additionally, it became a blueprint for the inventions in this new era – making devices personal.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik – the first artificial Earth satellite, starting a space race with the United States.

This race led to a rapid increase in demand for transistors and computers. However, a significant problem emerged – “the tyranny of numbers”.

As the number of elements in a circuit increased, the number of connections was growing much faster, which led to technological obstacles.

A microchip (also known as an integrated circuit) presented in 1958 became a solution for these problems. Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce are regarded as the fathers of the commercial use of this invention.

The former, who as the only one alive, was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2000, and got introduced as the person whose solution had launched the global Digital Revolution.

This time, the first commercial products to use microchips were hearing aids – which needed to be miniaturized.

Soon, in 1967 the market was flooded with the electronic pocket calculators produced by Texas Instruments that to this day is a significant player in that market.

Microchips enabled multifold of the computing power of ENIAC to be available in both military and consumer devices – from the space rockets to the handheld devices.

This rapid growth led to the well-known theory formed by the Intel CEO Gordon Moore (later called “Moore’s Law”) who in his 1965 paper said that the number of transistors that could be placed onto a microchip had been doubling every year and that this state is expected it to do so for the next ten years.

In 1975, he revised his forecast by changing it to 2 years, but his prediction turned out to be accurate for several decades.

Unveiling of a general-purpose microchip that could be freely programmed according to the preferences – the microprocessor by Intel (Intel 4004) in 1971 – accelerated the development of personal computers (PC) that soon became widely available to the general public.

One of the first was the 1974 Altair 8800 that according to the Microsoft founder Bill Gates “is the first thing that deserves to be called a personal computer”.

However, we cannot forget about Polish achievements in that field – primarily engineer Jacek Karpiński who presented his K-202 computer at the Poznań International Fair in 1971. His device could fit into a briefcase and rivaled the Western constructions.

However, being a competition to the government-backed company – Elwro, his invention was blocked by the communist Polish authorities and had never been widely introduced to the market.

Other machines produced by companies such as Apple, Atari, Commodore, and IBM helped to deliver personal computers to the masses in the 1970s and 1980s.

The VisiCalc spreadsheet was one of the early applications that accelerated the widespread adoption of personal computers by businesses.

The rise of portable information and communications technology

- Portable devices: Laptop, Tablet, and Smartphone

Another invention – the laptop, enabled easy remote work.

The first was developed in 1979 for Grid Systems Corporation and got used for NASA’s space shuttle program.

Commercial device considered as the one that paved the way to other constructions was Osborne 1 introduced in 1981.

Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) and later tablets – wireless touch screen personal computers had a similar aim.

One of the first commercially available devices was the 1993 Apple Newton MessagePad.

Tablets became widely adopted in the 21st century with the introduction of the 2007 Amazon Kindle and the 2010 Apple iPad.

In 1984, 8.2% of households in the United States had a computer. By 2015, it was 86.8%.

In 1990 Pew Research Center found that 42% of American adults used personal computers.

From the robotic arm on assembly lines to the automated teller machines (ATM’s) – there is no doubt that computers substantially changed the way we live and work.

In 2001, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that about 72 million Americans (about 53.5% of all the employees in the US) – used a computer at work, for example in engineering, besides obviously calculations, manual drafting was replaced with computer-aided design (CAD) increasing draftsman’s output on average by 500%.

Human labor has been widely substituted with computers in the multitude of industries, such as clerical jobs.

Not surprisingly, in the US there are currently more software developers than automobile mechanics or lawyers.

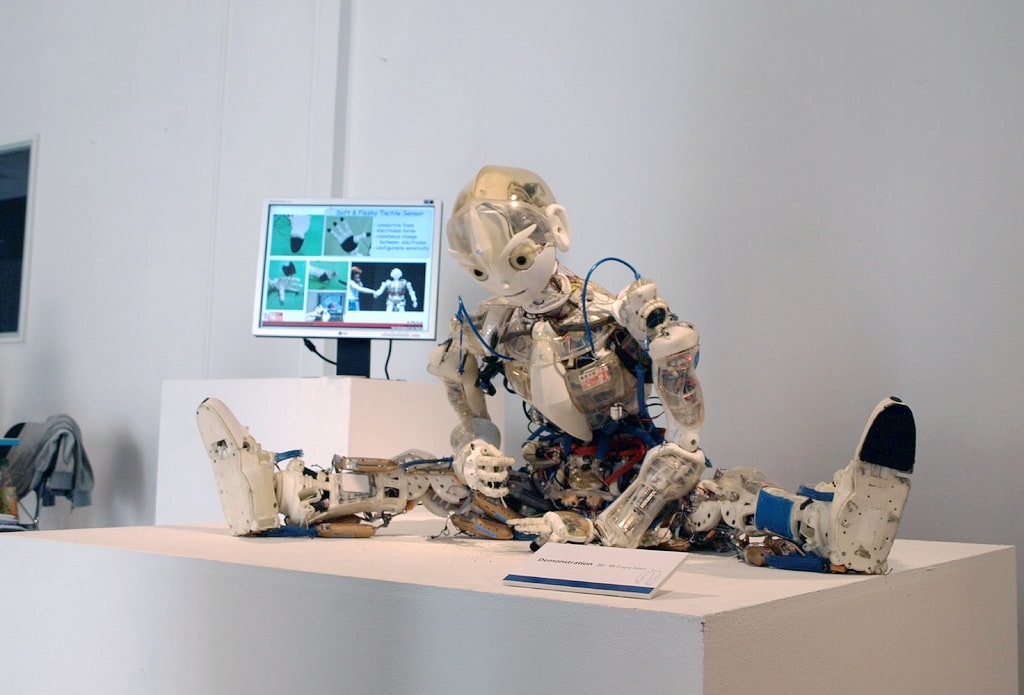

According to researches at the University of Oxford, 47% of total US employees are at risk of being eliminated by automation in the next two decades.

According to McKinsey&Company, while less than 5% of occupations can be entirely automated, 45% of the activities employees are paid for can be automated by current technology, including cashiers and retail workers – which presently is the most common occupation in the US – and can go away in the next two decades.

MIT scientist Andrew McAfee suggests;

Recent technological innovations have the potential to render humans obsolete with the professional, white-collar, low-skilled, creative fields, and other menial jobs.”

However, The World Bank’s World Development Report 2019 argues that technology is also paving the way to create new jobs.

However, the immense increase of human productivity and the creative potential resulting from the introduction of computers and their software would not have such a significant impact without the development in communications which enabled opportunities like distant collaboration.

Some might even argue that the latter has been even more important for humankind.

After all, according to Aristotle – “Man is a social animal”.

- Aristotle

However, there is no doubt that one specific invention is an integral element of the Digital Revolution – the Internet.

The Internet got developed as the triangular partnership between the military, universities, and private corporations whose aim after World War II was to create a military-industrial-academic complex.

One of the figures that helped to assemble this connection was MIT professor Vannevar Bush who was the head of the National Defense Research Committee and the Office of Scientific Research and Development.

According to MIT’s president Jerome Wiesner:

No American has had greater influence in the growth of science and technology than Vannevar Bush.”

Other notable research centers included the RAND Corporation, Stanford Research Institute, or Xerox PARC – to name a few.

Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider formed two theories that soon became vital for the development of the Internet – decentralized networks and interfaces facilitating human-computer interaction.

Soon, he was heading a team that designed the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment air defense system known as SAGE which cost more and had more people than the Manhattan Project that had built the atom bomb.

SAGE enabled interaction and communication between twenty-three centers in the United States, connected via phone lines which could provide early warning of an enemy missile attack.

In a paper published in 1960, Licklider wrote:

The hope is that, in not too many years, human brains and computing machines will be coupled together very tightly and that the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought and process data in a way not approached by the information-handling machines.”

In 1967, the Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency known as ARPA formed to fund scientific research created ARPANET – an experimental data network connecting different research centers via leased phone lines.

For the Pentagon and Congress who were funding the project, ARPANET had apparently also a strategic use – a decentralized network could withstand an eventual nuclear attack.

However, it is a popular myth that the original purpose of ARPANET was created because of this reason – research by Paul Baran of the RAND Corporation who was one of the inventors of packet switching concept is regarded as the source of this controversial.

In 1972, ARPANET got the first application – email, developed by Ray Tomlinson.

Soon, similar networks were created, but they were still not interconnected.

In 1973, Robert Kahn solved this problem by creating the universal Internet Protocol (IP) as well as Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) – and the Internet was born. However, the Internet was limited to military and academic uses.

Not until the development of personal computers and the introduction of modems – devices enabling ordinary people to connect their computers to the Internet via phone lines, the popularity of the Internet started to grow.

Soon, online communities such as the Whole Earth’ Lectronic Link (WELL) were born.

America Online (AOL) became one of the biggest internet providers – among other things by sending thousands of installation CDs to people.

At one point, AOL CD’s substituted for 50% of all CD’s produced worldwide.

When we went public in 1992 we had less than 200,000 subscribers; a decade later the number was in the 25 million range.” – said Steve Case.

By creating solutions such as the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991, the World Wide Web was born.

At the beginning of 1993, there were fifty Web servers in the world, and by October 1993 – five hundred.

In 1993, Mosaic became the first user-friendly web browser, enabling users to view images.

Other popular browsers included Yahoo, which was a big hand-compiled directory of websites. But there was a problem – in January 1994, there were seven hundred websites in the world, by the end of 1994 – a thousand, and in 1995 – 100,000.

In 1997, Larry Page and Sergey Brin improved it with their Google search engine that automatically ranks web pages with the PageRank algorithm, enabling the quick delivery of the results of the search.

In January 2019, Google had a 92.86% search engine market share.

However, widespread enthusiasm towards the Internet led to the so-called dot-com bubble – the rapid growth of equity valuations of Internet-based companies, which led to the market crash – by the end of 2001, many of public dot–com companies ceased to exist.

Soon, the term Web 2.0 got introduced, meaning the post-dot-com bubble World Wide Web, focused on social networking and content generated by users.

On the verge of the 21st century, the Internet became ubiquitous – in 1995 only 14% of US adults used the Internet, in 2000 it was 46%, in 2010 79%, and by 2014 – 87%.

According to the UN, 3.9 billion users were using the Internet in 2018.

According to other sources, global internet adoption passed 4 billion in 2018 – which is over half of the world’s population.

About a quarter of a billion users came in 2017.

In 2018, smartphones (mobile phones able to perform the functions of a computer, usually with a touchscreen interface, Internet access, and an operating system ready to run downloaded apps) were the preferred choice for going online – they accounted for more traffic than all the other devices combined.

An average smartphone user consumed 3 GB of data per month at that time – over 50% more than in the previous year.

It is not a surprise – two-thirds of the world’s population had a mobile phone (5.135 billion) in 2018 – over 200 million new users came in 2017.

The affordable cost of devices, mobile data plans, and ubiquitous access to the fast network lead to the growing adoption of this type of mobile phones which besides personal computers and the Internet – seem to be the third major element of the Digital Revolution.

1983 Motorola DynaTAC (Dynamic Adaptive Total Area Coverage) is regarded as the first practical non-vehicle setting mobile phone.

The company’s 1989 model MicroTAC became the first truly pocket phone.

In 1987, the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) was introduced.

Soon, 2G networks enabled text messages, invented in 1992 in the UK.

The 1983 IBM Simon became possibly the world’s first smartphone, and the 1997 Nokia 9000 Communicator with full QWERTY keyboard expanded this concept.

The same company introduced the first cell phone without an external antenna – Nokia 8810 in 1998 and in 1999 – Nokia 7710 that gave users web access.

The 1999 Benefon Esc! Became the first mobile phone with a GPS navigation feature. The 2000 Sharp J-SH04 was the first camera phone.

In 2003, the 3G standard was starting to become omnipresent, which enabled the further development of mobile Internet access and smartphones.

A significant shift came in 2007 when Apple introduced the iPhone – technically not the first smartphone, but the device that made smartphones mainstream.

According to the International Telecommunications Union’s Facts and Figures, in 2017 there were more mobile phone subscriptions than people.

In January 2018, 77% of Americans owned a smartphone.

Smartphone adoption is especially visible in developing countries – for example 34% of Senegalese adults owned it in 2018, which is up from 13% in 2013.

It is also worth to mention several often-confusing terms associated with the Digital Revolution.

These are, e.g.:

- Digital Native (a person familiar with digital technology from an early age),

- Digital Economy (economic activity resulting from online connections of people, data, devices and processes that changes the way of how conventional business is structured),

- New Economy (economy based on information rather than traditional sectors like manufacturing), Information Age (age when information is broadly available via computer technology),

- Information Revolution (development of technologies that led to the reduction of cost of obtaining and using information),

- Post-Industrial Economy (the shift of industrial economies from producing goods to the services),

- Sharing Economy (an economic system based on people sharing possessions and services, usually using the Internet),

- Gig Economy (a labour market characterized by the prevalence of short-term contracts or freelance work),

- Virtual Economy (system existing in a virtual environment enabling the exchanges of virtual goods, digital labor and currencies),

- Brick-and-Mortar (physical presence of an organization or business in a building, rather than only on the Internet),

- Digital Omnivores (users seemingly using different platforms to access the WWW), and

- Indigo Era (an era of economies based on creativity, ideas and innovation rather than natural resources – “indigo” comes from the term “indigo children” used to describe people with alleged unusual abilities).

As it has been presented in this subchapter, the Digital Revolution has changed the way we live and work.

On the other hand, it did not come without its drawbacks.

A possible digital dark age resulting from the obsolescence of file formats, fake news, financial scams, addiction, information overload, privacy, or copyrights concerns are becoming notorious problems associated with the development of technology in the 21st century. However, apart from society, the Digital Revolution has also changed business.

Novel business models have emerged often associated with new products and services – some of them becoming new disruptive innovations in themselves.

The concept of a Business Model and Disruptive Innovation

There are different theories regarding the purposes of business. According to the American Noble Prize winner economist Milton Friedman – the purpose of business is maximizing profits for the shareholders.

On the other hand, since 1970, when he presented his theory, our world has changed substantially.

Environmental, health and social impacts of business are becoming widely discussed issues in public debates.

The expression of this is the concept of “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR), which stipulates that besides profits a company should also be interested in society and the environment as well as the concept of “Triple Bottom Line” – an accounting framework proposed in the 1990s by John Elkington.

The latter, besides traditional profits, shareholder value and return on investment, also includes environmental and social aspects of the organization. However, there is no doubt that one of the purposes of setting up a business is by definition – earning money.

Yet, a much more difficult question is how to organize a company and create a product or a service that will produce this revenue?

After all, every business must have some formalized or implied model of operating. A business model is a manifestation of this need.

It became a popular contemporary concept used to analyze and set up new businesses.

Initially, the concept was associated with the e-business and new economy in the 1990s, but in 2001-2002 it started to gain more exposure.

According to Michael Lewis, the author of the book “The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story” a business model is like art – we can recognize it, but it can be hard to define it.

He gives one of the most straightforward definitions – how one plans to make money. However, different authors propose different interpretations of this phenomenon.

Peter Drucker, recognized as the founder of modern management despite not using the term business model, defined the underlying idea as the assumptions:

These assumptions are about markets. They are about identifying customers and competitors, their values and behaviour. They are about technology and its dynamics, about a company’s strengths and weaknesses. These assumptions are about what a company gets paid for. They are what I call a company’s theory of the business.”

Joan Magretta, a Senior Institute Associate at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, describes business models as stories that explain how enterprises work.

She suggests that the term became mainstream with the development of personal computers and the spreadsheet, which made way for people to model different components before launching a business.

Before, successful business models were created rather by accident than deliberate design.

According to Magretta;

Business modeling is the managerial equivalent of the scientific method – you start with a hypothesis, which you then test in action and revise when necessary.”

Authors of “The Business Model Navigator: 55 Models That Will Revolutionize Your Business” calls it a unit of analysis to describe how the business of a firm works.

Martin Geissdoerfer, Doroteya Vladimirova and Steve Evans from the University of Cambridge describe it as a simplified representation of the value proposition, value creation, value delivery, value capture elements, and the interactions between these elements within an organizational unit.

Alexander Osterwalder, the author of the “Business Model Generation”, describes it as the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.

Scholars Christoph Zott and Raphael Amit say that the business model depicts the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities.

Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen stated that a business model is built by four interrelated elements: customer value proposition, profit formula, essential resources, and key processes.

Finally, the Cambridge Dictionary explains a business model only as a description of the different elements of a business showing how they will work together effectively to make money.

On the other hand, a clear distinction between a business model and other related terms such as a revenue model, a business plan, a business strategy, and a corporate strategy is essential.

A revenue model explains how the company will generate revenue and be profitable.

While the business model is the “core content“, a business plan is a full guideline for action including more elements – the business model among them.

Business strategies are used to achieve different company objectives and are perpetually evolving.

Corporate strategy is the ideas and plans that a company has for future activities or the process of deciding about them.

Besides a variety of definitions, several frameworks have been created to “dissect” specific existing business models and create new ones.

One of the most commonly adapted includes “The Business Model Canvas” developed by Alexander Osterwalder, which is a graphic representation of nine different building blocks creating value in the organization.

- Key partners (the network of suppliers and partners),

- Key activities (the most important things a company must do),

- Key resources (the most important resources),

- Value propositions (products and services that create value for a specific Customer Segment),

- Customer relationships (the types of relationships a company establishes with specific Customer Segments),

- Channels (how a company communicates with and reaches its Customer Segments to deliver a Value Proposition),

- Customer segments (the different groups of people or organizations an enterprise aims to reach and serve),

- Cost structure (all costs incurred to operate a business model), an

- Revenue streams (the cash a company generates from each Customer Segment)145.

Osterwalder also proposes five popular types of business models: Unbundling, the Long Tail, Multi-Sided Platforms, Free and Open Business Models.

The first suggests that there are three different types of business within the company (customer relationship business, product innovation business, and infrastructure business) which can be unbundled into separate entities to avoid conflicts (e.g. private banking, mobile telecom companies).

The Long Tail means targeting the users of both popular and niche products to increase aggregate sales (e.g. eBay, Lego).

Multi-Sided Platforms bring together multiple groups of customers, creating a network effect (e.g. Visa, Microsoft Windows).

In Free Business Models, the substantial customer segment can benefit from a free offer. At the same time, it is financed by another part of the business or customer segment (e.g. Skype, Open Source).

Finally, Open Business Models create value by collaborating with outside partners (e.g. P&G).

However, by no means can we say that there is a closed catalogue of business models – it varies from company to company.

Yet, numerous established business models have been identified based on recurring patterns.

One of the most popular ontologies of them is “The Business Model Navigator: 55 Models That Will Revolutionize Your Business” by Oliver Gassmann and Karolin Frankenberger. They created it by analyzing 250 business models in various industries in the last 25 years.

The authors identified four crucial dimensions that make up a business model:

- the Who (who is the target customer?),

- the What (what is offered to the target customer?),

- the How (how the value is created?),

- the Value (how the revenue is created?).

These proposed business models are:

- Add-On: the core offering is priced competitively, but extras increase the final price,

- Affiliation: focus on supporting others to successfully sell products and benefit from successful transactions,

- Aikido: offering something diametrically opposed to the competition,

- Auction: selling a product or service to the highest bidder,

- Barter: exchange of goods without the transaction of actual money,

- Cash Machine: the customer pays upfront before the company is able to cover the associated expenses,

- Cross-Selling: services or products from a formerly excluded industry are added to the offerings,

- Crowdfunding: a product, project or entire start-up is financed by a crowd of investors who want to support the underlying idea,

- Crowdsourcing: the solution of a task or problem is adopted by an anonymous crowd,

- Customer Loyalty: customers are retained by providing value beyond the actual product or service itself,

- Digitization: ability to turn existing products or services into digital variants,

- Direct Selling: the company’s products are available directly from the manufacturer or service provider,

- E-Commerce: products or services are delivered through online channels only,

- Experience Selling: the value of a product or service is increased with the customer experience offered with it,

- Flat-Rate: a single fixed fee for a product or service is charged, regardless of actual usage,

- Fractional Ownership: sharing of a particular asset class amongst a group of owners,

- Franchising: the franchisor owns the brand name, products, and corporate identity, and these are licensed to independent franchisees,

- Freemium: the basic version of an offering is given away for free, encouraging the customers to pay for the premium version,

- From Push-to-Pull: decentralizing and thus adding flexibility to the company’s processes to be more customer-focused,

- Guaranteed Availability: the availability of a product or service is guaranteed, resulting in almost zero downtime,

- Hidden Revenue: the primary source of revenue comes from a third party, which cross-finances whatever free or low-priced offering attracts the users,

- Ingredient Branding: the specific selection of an ingredient, component, and brand originating from a particular supplier, which will be included in another product,

- Integrator: the control of all resources and capabilities in terms of value creation lies with the company,

- Layer Player: a specialized company limited to the provision of one value-adding step for different value chains,

- Leverage Customer Data: collecting customer data and preparing it in beneficial ways for internal usage or interested third-parties,

- License: efforts are focused on developing intellectual property that can be licensed to other manufacturers,

- Lock-In: customers are locked into a vendor’s world of products and services,

- Long Tail: instead of concentrating on blockbusters, the main bulk of revenues is generated through niche products,

- Make More of It: know-how and other available assets existing in the company are not only used to build its products but also offered to other companies,

- Mass Customization: individual customer needs can be met within mass production circumstances at competitive prices,

- No Frills: value creation focuses on what is necessary to deliver the core value proposition of a product or service,

- Open Business Model: collaboration with partners becomes a central source of value creation,

- Open Source: in software engineering, the source code of a software product is not kept proprietary, but is freely accessible for anyone,

- Orchestrator: the company’s focus is on the core competencies in the value chain. The other value chain segments are outsourced and actively coordinated,

- Pay Per Use: the customer pays based on what he or she effectively consumes,

- Pay What You Want: the buyer pays any desired amount for a given commodity, sometimes even zero,

- Peer-to-Peer: this model is based on cooperation that specializes in mediating between individuals belonging to a homogeneous group,

- Performance-Based Contracting: a product’s price is not based upon the physical value, but on the performance or valuable outcome it delivers in the form of service,

- Razor and Blade: the underlying product is cheap or given away for free. The consumables that are needed to use or operate it are expensive and sold at high margins,

- Rent Instead of Buy: the customer does not buy a product, but rents it,

- Revenue Sharing: firms’ practice of sharing revenues with their stakeholders,

- Reverse Engineering: obtaining a competitor’s product, taking it apart, and using this information to produce a similar or compatible product,

- Reverse Innovation: simple and inexpensive products, that were developed within and for emerging markets, are also sold in industrial countries,

- Robin Hood: the same product or service is provided to “the rich” at a much higher price than to “the poor”,

- Self-Service: a part of the value creation is transferred to the customer in exchange for a lower price of the service or product,

- Shop-InShop: instead of opening new branches, a partner is chosen whose branches can profit from integrating the company’s offerings in a way that imitates a small shop within another shop,

- Solution Provider: a full-service provider offers total coverage of products and services in a particular domain, consolidated via a single point of contact,

- Subscription: the customer pays a regular fee to gain access to a product or service,

- Supermarket: a company sells a large variety of readily available products and accessories under one roof,

- Target the Poor: the product or service offering does not target the premium customer, but rather, the customer positioned at the base of the pyramid,

- Trash-to-Cash: used products are collected and either sold in other parts of the world or transformed into new products,

- Two-Sided Market: a two-sided market facilitates interactions between multiple interdependent groups of customers,

- Ultimate Luxury: focusing on the upper side of society’s pyramid,

- User Designed: a customer is both the manufacturer and the consumer,

- White Label: producer allows other companies to distribute its goods under their brands so that it appears as if they are made by them.

In the age of the Digital Revolution, a concept which is often crucial for the analysis of contemporary business models is disruptive innovation.

This theory which has been called the most influential business idea of the early 21st century was proposed by Harvard Business School professor Clayton M. Christensen in his 1995 article ‘Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave’ and described further in his 1997 book ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’.

In essence, disruptive innovation is not a sustaining innovation that simply improves existing products. It transforms products making them affordable and available to more people, eventually disrupting the current market and replacing the former product.

For example, the first automobiles at the end of the 19th century did not disrupt the horse-drawn vehicle market, but the Ford Model T did.

Disruptive innovations are simple, convenient, and accessible. They don’t need to rely on technological breakthroughs – the business model is the key.

Markets with constraints that inhibit consumption can have good potential for these kinds of innovations.

Big players focus on sustaining innovations (upgrading existing products to attract wealthier clients). However, they often start to neglect regular users who just want a low-cost alternative.

Here, entrepreneurial firms with fewer resources (disruptors) enter with a primary offering which soon starts to upgrade their product and appeal to more customers.

When mainstream customers start adopting the product, the disruption takes place.

Disruption takes time; that is why incumbents often overlook disrupters.

The concept of Disruptive Innovation shows that the prevailing business adage “The customer is the king” might not always be strategically effective in the long-run – logical short-term decisions of management may cause the downfall of their companies.

One of the examples of disruptive innovation is steel mini-mills that disrupted traditional integrated mills after becoming commercially viable in the mid-1960s.

The integrated mills were capable of producing cheaper, but lower quality steel. However, steadily, mini-mills offered better quality steel and started to capture integrated mills segments.

Other examples include Toyota and Honda that started with economy car models adding later the premium ones, P&G that introduced whitening strips becoming a competition to expensive dental services or Nintendo that introduced the Wii – a simple console targeting traditionally non-gamers.

The concept of disruptive innovation is related to the earlier theory of creative destruction (also known as Schumpeter’s Gale) proposed by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942, who developed it from the works of Karl Marx in regards to capitalist development and the business cycle.

According to it, novel technologies, industries, and ideas in capitalism continuously displace existing ones which is necessary and natural for new markets and growth:

Capitalism (…) is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. (…) The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.” – Joseph A. Schumpeter

Another noteworthy concept regarding innovation includes Leapfrogging, developed by Drew Fudenberg, Richard Gilbert, Joseph Stiglitz, and Jean Tirole in 1983.

The main idea behind it is that sometimes innovations can enable new firms to “leapfrog” the established firms (which can also apply to cities or countries) who can move directly to more advanced technologies skipping the less efficient older ones.

For example, some countries in Africa adopted solar energy technology skipping the infrastructure based on fossil fuels.

Also, some developing countries moved directly to mobile phone technology, skipping the landline telephones phase.

This concept of leapfrogging includes mobile payment technologies which seem to have a significant impact on some economies – according to a study at MIT; mobile payments helped 194,000 Kenyans escape extreme poverty over eight years.

The concepts of business model, disruptive innovation, creative destruction and leapfrogging explained in this section appear to be essential for the analysis of contemporary emerging businesses – which in the age of Digital Revolution are more often than not based on technological innovations.

Prominent examples of contemporary disruptive digital business models

In recent years, digital services such as Spotify, Airbnb, Uber, Revolut or Amazon, changed the ways we consume media, travel, pay or shop, and are often becoming an integral part of our daily lives.

However, the aforementioned digital businesses are also prominent examples of disruptive business models.

The dissection of each company’s evolution and business model is crucial for the understanding of their impact on the contemporary business landscape – which often results in tangible “offline” consequences.

Spotify

Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, and life to everything. It is the essence of order and leads to all that is good, just and beautiful, of which it is the invisible, but nevertheless dazzling, passionate, and eternal form.” – Plato.

In the 21st century, these words do not seem to be deprived of their meaning.

Music is still a part of our lives and one of the most ubiquitous sources of entertainment. But today, music does not have to be played live – since approximately the 1870s we have access to a variety of recorded formats.

Through the years people could choose between, such as vinyl records, cassettes, or compact discs.

Devices such as the Walkman and Discman enabled people to take music with them everywhere.

Development of the Internet-enabled peer-to-peer filesharing services such as Napster introduced in 1999 (approximately 80 million users at its peak) paved the way for the new era of dematerialized music – and unfortunately music piracy resulting in reasonable outrage from the music industry.

In 2003, Apple introduced the iTunes store where users were able to legally download music for the fixed price of $0.99 per song.

On the other hand, the popularity of smartphones and mobile Internet access led to the development of music streaming services such as Deezer, Tidal, Apple Music or SoundCloud – where subscribers do not have to download a file or purchase an album to listen to music anymore.

Today, Swedish Spotify founded in 2006 by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon is the world’s biggest music streaming platform by the number of subscribers (36% of market share in 2018 – 191 million monthly active users).

Spotify provides a library of over 40 million songs thanks to licensing deals with the major music labels such as Sony Music, Warner Music Group and Universal Music Group.

It operates as a freemium business model. Free basic access includes advertisements and lower quality music.

Premium users have access to high-quality recordings, which are uninterrupted by ads.

Revenue is generated by premium subscriptions and advertisement.

These type of adverts include Sponsored Playlists, Branded Moments, Advertiser Pages, Sponsored Sessions, Audio, Branded Playlists, Display, Overlay, Homepage Takeovers, and Video Takeovers.

Royalties per stream are calculated based on factors such as contracts, country, and currency value. The average payout per stream is between $0.006 and $0.0084.

Along with piracy, streaming services disrupted the music industry.

In 2017, streaming revenue increased by 41.1% from 2016, and in 2018, music streaming revenue became higher than that of traditional streams such as record sales and downloads.

In 2019, Compact Disc album sales in the United States declined by 94% since peaking in 2000 and almost halved between 2000 and 2007.

Spotify overtook BBC Radio 1 in 2017 as the most-listened-to radio station in the UK.

What is more, in the US, one-in-five smartphone users have Spotify, which means that it has the most enormous reach of any mobile app.

However, music streaming might be the only way to reduce music piracy – in 2017, streaming music revenues quadrupled since 2013, while peer-to-peer filesharing penetration was decreased by half since 2013.

Taking into consideration convenience, quality, and the relatively low price of a subscription to music streaming services, music piracy is merely becoming obsolete.

Netflix

The Movie and TV industry has also been affected by streaming – American Netflix became a significant disruptor in that field.

Initially, Netflix, founded in the US in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Rudolph, was an online DVD rental service which introduced a subscription model as an alternative to the single-rental model of classic video bricks-and-mortar rental chains like Blockbuster.

In 1998, only 2% of American households had a DVD player. However, Netflix managed to acquire 1 million subscribers by 2003 – by January 2019, Netflix had over 139 million paid subscriptions worldwide.

They also introduced smart suggestion algorithms – Netflix can suggest to the customer new movies based on their past choices, thus creating a unique value proposition.

In 2007, Netflix introduced an on-demand video streaming service, for which it is best known today.

Users can choose between three plans: basic, standard, and premium differentiated by, e.g. video quality.

Netflix provides high-quality video through the use of strategically located servers across the world through cloud services provided by Amazon Web Services, thus avoiding problems with latency.

Since then, Netflix’s revenue grew from $1.2 billion to $6.8 billion in 2015.

In 2018, it reached $15.794 billion, a 35.08% increase year-over-year.

In 2010, one of the biggest video rental chains Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy – ironically a few years before, Netflix proposed to get acquired by Blockbuster, but the latter refused the deal.

In 2013, Netflix introduced Netflix Original – its productions (thus creating vertical integration – production + distribution) by releasing entire seasons of shows at once (it doesn’t rely on advertisements during the prime time) and unlike the competition, with the abundance of data – it could understand what customers want much better.

By 2017, Netflix expanded to 190 countries, but it did not enter all markets at once. Instead, it was growing steadily, starting with Canada in 2010.

In 2018, Netflix was responsible for 15% of the World’s Internet traffic.

The 2018 CNBC Economic Survey found that 57% of Americans pay for a streaming service, and Netflix constitutes 51% of subscriptions. It also shows that for every two people that rely on streaming, three rely solely on television.

In 2018, the number of subscribers to streaming services in the UK (15.4 million) became higher than the number of users of traditional TV services (15.1 million), while the US pay-TV subscribers penetration was at 78.1% – the lowest in over 15 years.

Today, Competitors of Netflix include streaming services such as YouTube, Hulu, Amazon Prime, Disney Plus and TV networks like HBO and Fox Entertainment.

While a trip to the cinema might still be a unique experience, Netflix’s business model clearly shows that we might be on the verge of disruption in the TV industry – probably because more and more people choose to avoid irritating commercials and watch their high-quality favourite shows on their preferred device and time schedule.

Airbnb

Travelling can be an expensive hobby, especially when it comes to the cost of accommodation. In the most popular destinations, hotel rooms might often be too pricey for many tourists.

However, we are no longer limited to hotels anymore – thanks to services such as Airbnb, which connects landlords of apartments and houses with prospective tenants, we can save a big part of our travel budget.

Airbnb was founded in San Francisco in 2007 by two roommates, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, who came up with an idea to rent their loft to provide a bed and breakfast to pay their rent, thus creating AirBedAndBreakfast.com.

One of the first significant opportunities to test their solution was the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver, where 80,000 people were expected to attend. However, Denver hotels had a hard time accommodating this vast number of guests at the same time.

An updated Airbnb website was launched two weeks before the event, and within a week it had 800 listings.

This action turned out to be an excellent marketing move – by March 2009, Airbnb had about 2,500 listings and 10,000 registered users.

By 2011, Airbnb was in 89 countries and had approximately 1 million nights booked. In 2012, Airbnb sold more per-night rentals than Hilton.

Today, there are about 6 million listings on Airbnb (more than the top five hotel chains combined), which is present in 191 countries.

Airbnb is considered by some as the biggest hotel company on the planet, despite not possessing any actual hotel rooms.

In 2016, Airbnb launched Experiences – an option for hosts to offer their city tours, local cuisine and other self-designed activities.

In 2018, Airbnb introduced Airbnb Plus and Beyond by Airbnb for high-end customers.

However, trust is still one of the most critical problems of this type of peer-to-peer business model, which might be the biggest obstacle in the way of their market penetration.

We bet our whole company on the hope that with the right design, people will be willing to overcome stranger-danger bias.” – said Joe Gebbia, the co-founder of Airbnb.

Because of that, Airbnb provides a rating and reviews system, secure payments, multi-factor account authentication, a 24/7 contact center operating in 11 languages, and conducts background checks.

In 2012, Airbnb introduced a $1 million damage protection guarantee for hosts. The revenue of Airbnb comes from the host service fee (3%), host experiences fee (20%), and guest service fee calculated based on factors such as the length of the stay or characteristics of the listing (0-20%).

According to the Earnest.com, in the US, Airbnb hosts make on average $924 per month, which is nearly three times as much as other participants of the most popular sharing economy platforms.

As a peer-to-peer/marketplace/aggregator business model, Airbnb provides an information-based offering, so it does not need to own real estate and vast infrastructure unlike big brick-and-mortar established hotel chains like Hilton or Mariott; thus it has much less fixed costs.

Besides the lower price of accommodation, Airbnb guests might have a unique local experience, which for many can be a reason to use Airbnb in the first place – this idea of affordability also shows that Airbnb can be regarded as a poster child of the sharing economy and collaborative commerce.

Uber

In case of Uber, the English idiom “Birds of a feather flock together” seems to be accurate.

Along with Airbnb, this San Francisco based company became one of the fastest-growing start-ups in history by sales, market value, and workforce.

Uber’s business model seems to be simple – primarily, it connects people via a smartphone application and a website with drivers who are willing to drive them using their personal vehicle. But unlike many cab drivers, all the cost regarding the car is on the side of the driver – Uber only provides a platform.

According to Uber, drivers are independent contractors, not employees, which has been the subject of criticism in several jurisdictions.

UberCab – as it was first called, was launched in San Fransico in 2009, by Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp.

Initially, the service was targeted towards high-end customers; it cost about 1.5 times as much as a taxi. However, in 2012, Uber unveiled UberX – a 35% less expensive option for the masses, and in 2013, allowed drivers to use their personal vehicles as part of it.

In 2014, Uber introduced UberRush – bicycle delivery in New York, and UberPool which enables users to split the ride and cost with other people riding the same route (becoming the Uber version of carpooling).

In 2015, UberEats was launched – an on-demand food-delivery service, which is among the most extensive food-delivery services, ranking second in the US.

In the same year, Uber established a research facility to build self-driving cars – one year later, Uber’s self-driving vehicles debuted in Pittsburgh.

In the future, driverless cars might reduce the number of Uber human drivers, resulting in even lower prices for the customers.

UberFreight launched in 2017 and connects carriers/truck drivers with shippers.

In 2018, we also saw an introduction of UberHealth – a partnership with healthcare organizations to provide transportation for patients.

Currently, the standard Uber mobile application services include UberX, Van, Select (premium cars) and Black (luxury cars).

There are also several other local variations of Uber services.

Now under development is UberAIR/UberElevate, a service providing short flights with Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) aircraft.

In the words of Uber’s CEO Dara Khosrowshahi:

What we are looking to build at Uber is essentially your A to B platform for anyone wanting to get from one place within an urban destination to another place (…) Cars are to us what books were to Amazon. Just like Amazon was able to build this extraordinary infrastructure first on the back of books and they went into additional categories, you are going to see the same thing coming in Uber.”

We are in a business of delivering cars in 5 minutes. Once you are delivering cars in 5 minutes, there is a lot of things you can deliver in 5 minutes.” – adds Travis Kalanick, previous CEO of Uber.”

The price of an Uber ride is calculated based on the base rate, booking fee, plus it depends on the time and area – it is also influenced by the local supply and demand.

Uber’s revenue comes from the driver’s variable service fee. To assure safety, Uber provides 24/7 incident support, an emergency assistance button, following ride by family, 2-way ratings, GPS tracking, and a driver’s background check (review of a photo ID and other relevant documentation).

Drivers might also be occasionally ordered to take a selfie when logging on to Uber (Real-time ID Check). The application also enables tips and giving compliments to drivers.

Feedback is crucial – an Uber driver can be automatically penalized by the system when their customer rating falls below 4.6/5. However, bad passengers can also be temporarily banned.

Like Airbnb, Uber also does not own many physical assets despite being among the world’s most extensive car services – since its launch in 2009. By the beginning of 2014, Uber booked 200 million rides, 1 billion by the beginning of 2016, and 2 billion 6 months later.

During this time, the number of employees grew from 550 to 8,000.

In 2012, the company was valued at $350 million.

In 2014, it was $18 billion – 2 years later; its valuation had tripled to $68 billion, which was more than any other privately held start-up company in the world.

In 2018, it was $72 billion. Because of that, Uber can be easily labeled as a “unicorn” – which is a popular term for start-ups that have achieved a valuation of over $1 billion.

In the same year, Uber was available in 65 countries, and over 600 cities worldwide with about 15 million Uber rides completed each day. Furthermore, its market share of the US was estimated at 69-74%.

However, Uber also has its rivals, such as Lyft, Grab, and Didi Chuxing in the Southeast Asian and Chinese markets – the latter controls 90% of the market in China.

In 2018, CNBC rated Uber 2nd on its list of most disruptive companies in the world, only after SpaceX.

The impact of Uber can even be seen in the home of the worlds most iconic taxis; New York, where in August 2018, 436,000 Uber rides took place per day, 122,000 Lyft rides, and only 275,000 taxi rides.

Uber’s business model also includes quite unusual marketing actions such as teaming up with animal shelters in the US when riders could spend 15 minutes with kittens (UberKittens), on-demand donation pickups (UberSpringCleaning), offering rides in the famous DeLorean from “Back to the Future”, or free rides for Saudi Arabian women when for the first time in history they were allowed to vote in 2015.

The impact of Uber resulted in coining the term “Uberisation” – a euphemism used to describe highly tele-networked businesses that achieve their peak efficiency in operations by utilization of direct peer-to-peer client-provider on-demand transactions, quality-assuring rating systems, and the elimination of middleman roles.

These types of companies, unlike other conventional businesses, are often characterized by a near-zero marginal cost, which means that the cost of producing an additional unit of a good or service after fixed costs is minimal.

The development of smartphones and geolocalization technology, the convenience of the app, and network effects helped Uber to become one of the leading disruptors in the often- inefficient transportation industry.

What is also inspiring in Uber’s disruptive business model is the successful creation of additional services based on the already developed technological foundation – if we have a platform, we mastered the technology which many people use – so why not expand into other categories and use it to deliver things like food and cargo?

Revolut

“Fintech” became a popular buzzword in the contemporary financial industry.

In general, Fintech means innovative computer programs and technology used to support banking and financial services.

The 2008 financial crisis caused a loss of trust in traditional financial institutions, which led to the substantial increase in the development of financial technology solutions – according to CNBC; Fintech investment went from $1.8 billion in 2010 to $19 billion in 2015.

In the EU, investment in Fintech companies hit $34.3 billion in 2018, which is up 400% from the year before.

Also, one in three people across twenty major economies report using at least two Fintech services in the last six months.

Currently, Fintech is thought to be causing the biggest revolution in the financial industry since the introduction of mainframe computers in the 1960s.

Among these disruptive technologies within Fintech are mobile applications providing alternative digital banking services. Revolut, founded in 2015 in the UK by Nikolay Storonsky, is one of the fastest-growing “neobanks” which currently operates in 28 European countries and is valued at $1.7 billion.

In 2018, the company had 3 million customers and was opening approximately 7,000 new accounts every day. The company handled $4 billion in monthly payment transactions in February 2019, which was up 33% from October 2018.

With Revolut, users can open an account within a few minutes, transfer and exchange money in 29 currencies with the lowest interbank exchange rate, instantly send and request payments from peer-to-peer, split the bill, buy an insurance (from £1.00 per day), check interest rates, set up a monthly budget, or automatically save money by rounding up payments to the nearest whole number (“Vaults”).

A physical card is sent to users, which can be used for payments and withdrawing money from the ATM.

Revolut enables creating a virtual card, freezing the card, disabling contactless/swipe/online payments, or location-based security.

Users can choose between three types of accounts: Standard (free UK and Euro IBAN account), Premium (e.g. premium card, higher free ATM withdrawals) and Metal (e.g. exclusive Revolut Metal card, 0.1% cashback within Europe and 1% outside Europe on all card payments, and private concierge services).

There are also separate accounts and services for businesses.

Revolut’s revenue comes from its users’ monthly payments, a 0.5% exchange fee, and a 2% ATM withdrawal fee above specified amounts.

According to Storonsky, Revolut saves on average 50 EUR for every 500 EUR that a user spends. He also claims that Revolut reached almost 1 million users in two years without any marketing.

Our focus, since we launched, has been to do everything completely opposite to traditional banks.” – said Storonsky.

In 2018, Revolut obtained a European banking licence approved by the European Central Bank, which means that it is authorised to accept deposits and offer consumer credit.

According to the author of Disruptive Innovation theory, Clayton Christensen –

In a bank you have a backend of a bank when you do all the functional things that just have to happen. It has to be there and is heavily regulated. And then there are business units in a bank that provide various services or products. And historically, the connection between the services and the backend is an interdependent connection, meaning it makes things slow, but there is when you make money. And then, at the next interface between the people that provide the services and the customers, historically that has been an open modular interface.”

Thanks to companies such as Revolut, Monzo (its UK competitor), N26 (its German competitor) or Square (which allows individuals and merchants to accept offline debit and credit cards on their mobile device or computer), we can see the beginning of disruption in this area.

Henri Arslanian, Adjunct Associate Professor at Hong Kong University, claims that Fintech companies try to tackle a gap between what banks are offering and what the customer is expecting in terms of convenience. However, Fintech startups don’t want to control the backend part of the banking industry (e.g. taking deposits) – they want to control frontend – the customer-facing part – which creates a unique banking model of the future.

Traditional banks might become commoditized utility providers to Fintech startups. Over the next ten years, 30-50% of banking jobs might disappear.

In cities like Detroit or Miami, more than 20% of households are unbanked. For the first time, these individuals can be offered financial services – over the last five years, about 700 million people went from being unbanked to banked, largely thanks to the Fintech industry.

Amazon

There is no doubt that the business founded by one of the wealthiest people in modern history must be worth examining. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, was worth approximately $150 billion in 2018, which was $55 billion more than the founder of Microsoft – Bill Gates.

The big question is – how did he manage to acquire this wealth by founding the company that is disrupting the worldwide retail industry, and was called by Yahoo Finance “Perhaps the most ambitious company in American history”?

In its essence, Amazon is a leading example of a Hypermarket Business Model. Its main activity is selling books, music, electronics, and other goods directly or indirectly between retailers and Amazon’s customers via its e-commerce platform.

However, the company has come a long way since it (initially named “Cadabra”) was launched in 1994 by Jeff Bezos and his ex-wife MacKenzie in Seattle as an online bookstore.

This idea soon turned out to be successful – within the first month, Amazon sold books to people in all 50 states and 45 additional countries.

The company had almost no inventory back then – Amazon was ordering books bought by customers and shipping it to them.

Some of these books appealed to relatively few people, but due to the e-commerce platform and economies of scale – Amazon could generate significant revenue out of this segment (“Longtail”).

But why did Amazon start with books?

According to Jeff Bezos:

They were pure commodities; a copy of a book in one store was identical to the same book carried in another, so buyers always knew what they were getting. There were 2 primary distributors of books at that time, Ingram and Baker and Taylor, so a new retailer wouldn’t have to approach each of the thousands of book publishers individually. And, most important, there were 3 million books in print worldwide, far more than a Barnes & Noble or a Borders superstore could ever stock.”

Because Amazon’s ratio of fixed costs to revenue was noticeably better than that of its brick-and-mortar competitors, the company quickly became a significant threat to the big bookstore chains like Barnes & Noble.

In 1996, Amazon reached 180,000 customer accounts, and 1,000,000 in 1997. In the same time, its revenues grew from $15.7 million to $148 million.

In 1997, the company went public with a message to investors that due to extensive investments “substantial operating losses for the foreseeable future” were to be expected.

In the following year, Amazon expanded into selling music by introducing 125,000 titles and enabled customers to listen to the songs and view recommendations before ordering.

In 1999, Amazon patented the “1- Click” technology which enabled customers to buy items online with a click of a mouse and enabled third-party sellers to sell their new or used products on the Amazon platform (now called Amazon Marketplace).

A customer could choose if they want to buy the item from Amazon or from a third-party seller. If the customer chose the latter, Amazon would collect a commission.

In the same year, Jeff Bezos became the Person of the Year according to Time Magazine that called him the “King of Cybercommerce”.

Soon, Amazon expanded into other categories, such as clothing, electronics, toys, and kitchenware.

In 2005, Amazon introduced Amazon Prime – a $79-a-year loyalty program which included free 2-day shipping of orders (and made customers spend more).

Besides that, Amazon Prime now also includes Netflix and Spotify-like media content streaming services.

Fast delivery, an abundance of items, data-driven products recommendations and review features which created a vast community of customers, helped Amazon to become one of the leading e-commerce players.

In 2018, Amazon’s $258.22 billion US sales accounted for 49% of all US online retail sales and 5% of all US retail sales.

In 2017, the company had 80 million Amazon Prime members in the US which is an equivalent to 64% of all US households while in 2016, 55% people in the US started their online shopping process on Amazon.

However, at the time of writing, Amazon is much more than just an e-commerce platform.

According to Jeff Bezos – the goal of Amazon is to be a technology company, not a retailer.

In 2002, the company launched Amazon Web Services, which offers data for developers and marketers, computer processing power and data storage for companies. Clients of Amazon Web Services include Netflix, CIA, and NASA.

Currently, Amazon dominates cloud hosting services being as big as its next four competitors combined.

Amazon Web Services is the most lucrative part of the company – in 2018, it generated $25.7 billion, which is more than the revenue of McDonald’s.

In 2006, the company introduced Fulfilment by Amazon – a service that manages the inventory of small companies and individuals that want to sell through Amazon.

In 2007 came Kindle – Amazon’s e-reader, which changed the way we consume books – in 2011, Kindle e-books were outselling all printed books at Amazon.

In recent years, the company introduced drone delivery, Amazon Echo, powered by virtual assistant Alexa (an internet-connected voice-controlled device which can be used, e.g. to order products on Amazon), and is expanding into industries such as event tickets, pharmaceuticals, home services, payments, and many more.

The significant element of Amazon’s business model is the acquisition of other companies.

In 2008, Amazon acquired an audiobooks company Audible which currently holds over 40% of the audiobook market.

One year later, it bought an online shoe retailer Zappos – effectively getting rid of its competitor in that market.

In 2012, Amazon acquired Kiva Systems, a maker of warehouse robots, to automate its fulfilment centers.

In 2013, it bought Goodreads, the leading social network for book enthusiasts.

After rolling out 2,200 Amazon grocery stores in 2016, in 2017, the company bought an American supermarket chain Whole Foods securing its position in the highly-competitive grocery delivery business and challenging big supermarkets like Walmart.

Currently, Amazon is the largest Internet company by revenue in the world despite not producing any profit until 2001. That’s because Jeff Bezos emphasizes customer experience over profits – for example each employee, every two years, is obliged to spend two days on the customer service desk.

It’s all about the long term – gaining customers is more important than a profit.

Thanks to this approach as well as economies of scale, an abundance of data about users, and systematic entering new industries with its technological infrastructure, Amazon’s business model turned out to be one of the most successful in the Age of Digital Disruption.

The future of business in the age of digital disruption

Despite their often profound positive effects for the customers, disruptive digital business models of the 21st century are also subjects to criticism and vivid public debate.

While disrupters perceive their service as innovative and only more efficient, incumbents usually want to prevent them from acquiring their market share.

This naturally results in clashes between these two parties. On the other hand, science and technological advancement is continually progressing.

Every year, we can see an emergence of new business models that make use of novel technologies, some of which, after their ubiquitous adoption, might be the source of next significant disruption in specific industries.

Legal and economic challenges of disruptive digital business models

Disruptive innovation usually results in experiencing a significant backlash, and the founders of the businesses mentioned above know it best.

Spotify, Netflix, Airbnb, Uber, Revolut and Amazon – in recent years, all of them had to face various types of minor or major legal and economic challenges – some of which leading to the involvement of national or local governments and new legislation.

Spotify

Challenges that have to be faced by Spotify are much better known, primarily – the problem of non-satisfactory royalties for artists.

The average payout to the holder of music rights per stream (who can be divided between the record label, producers, artists or songwriters) in Spotify is between $0.006 and $0.0084. However, Spotify is not the worst – in comparison, YouTube average payout is $0.0007 while Tidal pays the most – on average $0.0150 per stream.

Spotify pays money via a “pro-rata” model – so for example, if an artist’s songs account for 2% of all subscriber plays in a month, subjects who own the rights to these tracks will get 2% of Spotify’s user-paid money.

According to the 2015 study by music trade body SNEP and EY, music labels keep approximately 73% of Spotify Premium payouts, writers or publishers receive 16%, and artists only 11%.

According to UC Irvine professor Peter Krapp, it takes about 4 million Spotify streams for an artist to make minimum wage in California.

Another estimate stated that 1 million plays on Spotify equal to around $7,000. Because of that, in 2018, the US Copyright Royalty Board ruled that artist should be paid more. According to its ruling, streaming companies must pay at least 15% to music publishers (previously, streaming companies had to give a minimum of about 10% of their revenue to music publishers).

In the beginning, Spotify needed money from the big record labels, but today, Spotify is a big international player providing distribution of music in a digital format.

Some suggest that streaming services should start to act more like record labels and have most of the deals directly with artists, not major record labels that can take even 70% of an artists’ royalties.

Spotify has to communicate that they are the labels’ no. 1 partner, there to help artists and labels find success (…) But at the same time, they present themselves as part of a future which they imply doesn’t necessarily include record labels.” – said Mark Mulligan, a digital media analyst at Midia Research.

On the other hand, according to The Guardian, the top 10% of artists dominate 99% of streams on Spotify.

Ed Sheeran, after the release of his 2017 album got 16 tracks in the Top 20. Blake Morgan, an independent musician and a label owner, said: “The streaming model as it stands now is fundamentally stacked against middle-class artists and emerging artists (…) 90% of the revenue is going to 1% of the artists”.

Due to the Spotify’s algorithms which might cause some kind of “gatekeeper effect” it can be hard for emerging artists to achieve success.

Some even suggest that Spotify creates fake artists without any profile outside the platform to save on royalties. Spotify was also accused of “pay-for-play” practices.

Because of these controversies, some artist decided to withdraw their music from Spotify. These include Neil Young, Radiohead singer Thom Yorke, Taylor Swift, or Swedish musician Magnus Uggla who said that after half a year he earned “What a mediocre busker could earn in a day.”

Talking Heads singer David Byrne adds: “If artists have to rely almost exclusively on the income from these services, they’ll be out of work within a year”.

Besides, in August 2015, Spotify made a controversial change in its privacy policy by introducing a statement: “With your permission, we may collect information stored on your mobile devices, such as contacts, photos, or media files. Local law may require that you seek the consent of your contacts to provide their personal information to Spotify, which may use that information for the purposes specified in this Privacy Policy.”

However, companies like Kobalt are trying to change this state of affair. This independent rights management and publishing company founded in 2000, unlike other major music labels, does not own any copyrights; it collects royalties directly from services such as Spotify or YouTube and allows artists to manage their rights directly.

In 2015, Kobalt was the top independent music publisher in the UK and the second overall in the US with approximately 600,000 songs and 8,000 artists under its umbrella (e.g. Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan or Prince).

We’re unique in being 100% transparent, and with a new concept: We’re going to pay artists. And that means we’re a service provider. (…) If you’re a songwriter and you go to a major publisher, they own your rights. To maximize value for them is to minimize the amount they pay you. It’s built in the structure. So think about that. There’s you with limited resources. And then there’s the company with all the data, all the resources, and they have your money too. They are dis-incentivized to pay you. (…) In economics, Principal Agent Theory says that aligned interests increase returns. So it was absolutely clear that our interests should be aligned with songwriters. Corporate is here to maximize your cash flow and be 100% open. You don’t need to sue us to get your data — it’s all there. You have everything.” – said Willard Ahdritz, founder and CEO of Kobalt.

Netflix

In 2006, Netflix organized a competition to introduce a better system of movie recommendation based on the customers’ data to improve the old one – Cinematch.

In 2010, the company cancelled the contest because of concerns regarding the privacy contestants had access to data that could identify the customers. This activity resulted in a lawsuit from KamberLaw L.L.C. and brought the attention of the Federal Trade Commission.

Another Netflix controversy concerns so-called “Throttling” – Netflix’s DVD allocation practice was giving priority to users who were renting fewer discs per month. Users that were renting more discs could see delays or other problems with their order.

This resulted in the 2004 consumer class action lawsuit, Frank Chavez v. Netflix, Inc. accusing Netflix of false advertising because of its marketing statements such as “unlimited rentals” and “one-day delivery”.

The proposed settlement for this Netflix controversy, without admitting wrongdoing, included a free one-month service upgrade for current subscribers and a coupon good for a free month of service for those who had been Netflix subscribers before January 15, 2005.