Getting around in the early 19th century was difficult, for the country was vast with mountains and rivers, often making travel more difficult.

Pockets of settlement, such as St. Augustine, Santa Fé, and the missions in California, had no contact with the English-speaking areas. The latter had settled from the eastern shores into parts of the interior.

Settlers first came to harbors

Some stayed, but some moved into the interior by using some rivers or following the trails created by the immigrants who had come centuries before.

Even in the early 19th century, settlement had not much reached beyond the fall line in Virginia and the Carolinas. Although Savannah was settled by 1773, North Georgia was just getting settled in 1800.

Tiny New England was slowly filling out, but western Massachusetts was frontier territory when Daniel Shays led a rebellion against taxes in the 1780s.

New York had the river corridor of the Hudson River and then the trails created by the Iroquois on the route the Erie Canal would take.

Free land was given as a reward for service in the Revolutionary War or the right to participate in a lottery.

Land speculators in the 18th century were active, for they had to sell land in the West (today, the Midwest and the western South) to make money. The Ohio and Mississippi Rivers enabled some people to get to new territory.

People did move into new territories, but the cost was relatively high, and they had to have a significant potential payoff to move.

Settlements tended to be self-sufficient, with precious little contact with the outside world.

One’s closest neighbors could easily be a day’s ride if one could afford a horse or several days if one had to walk. Extended families clustered together for safety and companionship.

The Cleveland’s, Isbell’s, and Dickson’s settled in north Georgia (now in South Carolina) after the Revolutionary War.

Benjamin Cleveland led one of the militia colonels who won the Battle of Kings’ Mountain in the Revolutionary War. He moved after the war when he discovered that his North Carolina land titles were invalid. So he, his family, and his entourage moved. Very few were Revolutionary War heroes, but this group migration was typical.

(Collage of the American Revolutionary War)

Public land sales (land owned by the national government) increased in the first decades of the nineteenth century.

The Harrison Land Act of 1800 was more liberal than its predecessor.

A person only had to buy 320 acres (half-section) at a time instead of 640 acres, paying 50 cents per acre down and the rest of the $1.50 an acre in instalments in four years.

The Land Act of 1804 lowered the minimum purchase amount to 160 acres.

Cheapening the land created a boom in land sales. In 1800, the US government sold 67,800 acres; in 1813, 500,000 acres, in 1818, 1,306,400 acres; and in 1819, 3,491,000 acres.

The population on the west side of the Appalachian Mountain chain doubled between 1810-1820 and then doubled again between 1820 and 1830. Indiana, Illinois, Alabama, Mississippi, and Missouri became states because the population had grown so much.

The key to the development of this West was a good transportation system, one which would allow people and goods to move relatively quickly and cheaply.

Time and distance were a real problem in 1801

For example, it took four days to go from New York City to Boston or Albany or Washington, DC, a week to get to Pittsburgh, and twenty-eight days to get to Detroit.

The problem also gets illustrated by the cost of shipping goods in the more settled eastern parts of the United States.

In 1816, the cost of shipping a ton thirty miles overland in the United States was the same as shipping the equal ton to England. The average price was seventy cents per ton per mile (a ton-mile).

In 1817, the cost of shipping a bushel of wheat from Buffalo, New York, to New York City was three times the market value of the bushel of wheat. It was six times for a bushel of corn, and for oats, it was six times.

Transportation costs across land were prohibitively expensive except for very high-priced or precious items.

Most goods—agricultural, handcrafted, or manufactured—were sold locally.

In farming communities in which most people lived, a family grew crops and livestock to feed itself.

Unlike Europe, all roads didn’t lead to Rome in America; they had to get built from scratch

The roads, such as they were, were built and maintained by local people by towns, for the states had few sources of revenue and found it difficult to raise taxes.

This tax was an unsatisfactory solution for anyone traveling very far because different towns along a route would have various commitments to finding revenue sources sufficient for the task at hand.

Turnpikes were the first solution

In Pennsylvania, the state started building the Philadelphia to Lancaster Turnpike in 1792 and opened it in 1794. It was financially successful, setting off a wave of turnpike construction.

Most of the turnpikes were private toll roads organized as joint-stock companies. States tried to ensure that they could get built.

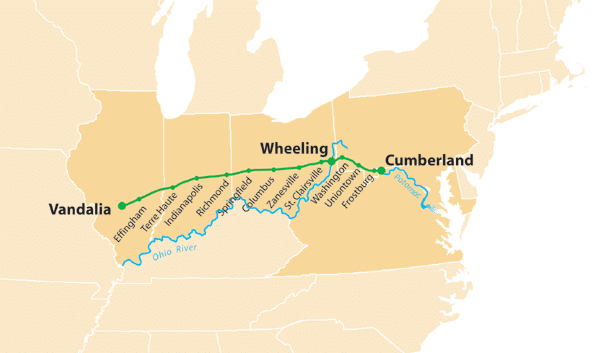

At the national level, the US government began funding the National Road (today roughly US 40) in 1811.

The road started in Cumberland, Maryland and meandered to present-day Wheeling, West Virginia, on the Ohio River.

By 1833, it had reached Columbus, Ohio. Although these roads helped, shipping freight across them was expensive.

(Map of the National Road)

Shipping by steamboats was cheaper and faster.

If one used a wagon, there was the cost of lifting the cargo off the ground and keeping it there as well for moving the vehicle forward.

A water vessel had the advantage of only having the cost of moving forward because the water lifted the cargo.

Men had long used boats powered by pushing poles or by sail, but neither means of propulsion could always get used.

The shallow draft steamboat, however, could carry large amounts of cargo even against the flow of a river.

Robert Fulton‘s Clermont proved the practicality of steamboats in 1807.

By 1820, there were 60 steamboats on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and countless others elsewhere.

Steamboats could ply the waters of lakes and rivers but could not go where there was no waterway, so people built them—canals.

The first successful one was the Erie Canal in New York, stretching from the Hudson River at Albany westward to Buffalo on Lake Erie, opening the old Northwest and connecting it to New York Harbor.

The canal started in 1817 and turned a profit long before it was finished in 1825.

It sparked a canal boom as others tried to mimic its success.

Canals were only profitable if they connected two existing bodies of water with goods to be shipped from each end, as was the case of the Erie Canal.

(Painting of the Erie Canal getting built)

Railroads provided the solution, for they could be built anywhere and carry many tons of freight and people.

Americans borrowed from the English experience, where the first roads were built. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O;) were the first in 1828.

By the 1860s, many railroads and some 31,000 miles of track were laid.

What difference did it make?

If one were going from Cincinnati on the Ohio River to New York City in 1815 by keelboat and wagon, the trip would take over fifty days.

By 1850, however, the same trip could be made by steamboat to New Orleans and then a packet ship in twenty-eight days or via the Ohio and Erie Canals and then the Hudson River in eighteen days, or, better yet, by railroad in six to eight days.

Similar gains got made in the cost of shipping. Where the price of a ton-mile in 1815 was 70 cents, in the 1850s, it had dropped to between 2 and 9 cents if transportation by railroad and one cent if shipping via canal.

Had state governments, and the national government to some extent, not abandoned free enterprise theory and intervened in the economy, the transportation revolution would not have occurred.

The Hamiltonians, the conservatives of the day, had argued that the government should ally itself with the rich or well-born.

When he had the Bank of the United States created, this was a goal that the liberals, led by Thomas Jefferson, opposed.

Hamilton also wanted to help the better off by levying a stiff tax on imports, a tax which the ordinary people would also be paying, to make people buy domestic goods, even if they were inferior.

In transportation, states bought stock in transportation companies or otherwise facilitated the selling of stock; they granted monopolies; they built canals; they subsidized railroad companies; and they granted businesses corporate charters, a business device which allowed the raising of large amounts of capital but limited liability if the business failed.

Moreover, they charted banks, institutions which created money and expanded credit, all necessary for building transportation networks, an inherently expensive undertaking.

Nevertheless, long-term investment in transportation played a significant role in shaping the USA into the leading economy in the world.