The “new economy” (digital economy, knowledge economy) both affords fresh opportunities for strategic economic development and demands fundamentally different approaches by economic development agents and agencies (Collits 2017a and b).

The new opportunities revolve around the emergence of regionally locatable, platformed businesses that are easy to start and scale, can reach global customers with ease and which offer high skilled, well-remunerated work.

High growth businesses in high growth sectors of the economy provide the twenty-first century “sweet spot” for economic development.

Activity can occur both in developing these businesses (capability) and in growing the entrepreneurial ecosystems (culture, services) that are needed to support them (Collits 2017a; Mason and Brown 2015; Miles and Morrison 2016).

The demand for new economic development approaches is the result of the massive, ongoing and accelerating disruption of existing (legacy) businesses and sectors that needs to be recognised, analysed, confronted and addressed.

So building a digital economy is a question of both opportunity and necessity. It is for the benefit of both economy and community, of businesses and of the workforce.

Building a digital economy involves both business and investment attraction and growing local capability, aka “economic gardening”. It demands action by a wide range of stakeholders, led in collaborative activity by economic development agents and agencies.

Background – the new economy

The futurist Gerd Leonhard has perhaps best captured the nature and significance of the new economy in a compelling video. See the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ystdF6jN7hc

Two other observations sum up the sweep of the changes in business models now occurring:

Today, we stand on the threshold of an economy where the familiar economic entities are becoming increasingly irrelevant. The Internet, and new Internet-based firms, rather than the traditional organisations, are becoming the most efficient means to create and exchange value. (Simon Bond)

For a similar view:

For most of the developed world, firms, as much as markets, make up the dominant economic pattern. The Internet is nothing less than an extinction-level event for the traditional firm. The Internet, together with technological intelligence, makes it possible to create totally new forms of economic entities, such as the “Uber for everything” type of platforms / service markets that we see emerging today. Very small firms can do things that in the past required very large organisations. (Esko Kilpi)

Critically for economic development (theory AND practice), new business models mean that new approaches to the support of businesses through economic development activity are also needed.

These developments and their implications need to be properly understood by those leaders and organisations who employ and supervise economic development professionals.

The “digital economy” has been defined (by Don Tapscott, the inventor of the term) as “the age of networked intelligence” (Tapscott 1994 and 2015).

Tapscott’s insight was to see the power of networks in a then-emerging age of information and speedy connectivity – the radical connectivity of ideas to resources; firms to customers; firms to suppliers; customers to other customers; firms to collaborating firms; all typically enabled through newly developed digital platforms (including open source software) and a freshly emerging collaborative, “pay-it-forward” business mindset.

Bukht and Heeks provide a useful summary of definitions and conceptualisations of the digital economy (Bukht and Heeks 2017).

Digital transformation is only one element of the new world of business and work, the so-called “second machine age“ (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014).

The new economy has also been termed, variously:

- A knowledge economy;

- An information economy;

- A digital economy;

- A sharing economy;

- A gig economy;

- An open + networked economy;

- The exponential economy;

- A platform economy;

- A peer-to-peer economy

- An on-demand economy (Collits 2017b).

The reason that the knowledge economy differs from the old economy and offers regions fundamentally new ways of achieving economic growth and prosperity is that there are increasing returns and long run growth to be gained from ideas and knowledge (Romer 1986).

Now the greatest source of value to companies is knowledge, not physical assets. Technology provides the platform for companies and for locations/regions to maximise value from ideas and knowledge.

Firms themselves are evolving and often disappearing. Jobs now come mainly from young firms and small but growing firms.

It is now easy to start and grow a firm because of the power of ideas + technology harnessed to support the power if ideas and knowledge.

Key elements of a digital economy strategy

Accessing affordable digital and knowledge infrastructure, building business and community skills, attracting and growing digital business skills across businesses and in the workforce, and attracting and growing high technology businesses, are the key tasks of a digital economy strategy.

The principal challenges for provincial regions in relation to digital economy strategy are:

- The low density of high tech companies and of entrepreneurs;

- Under-developed networks;

- Under-developed ecosystems;

- Thin services to start-ups and entrepreneurs;

- Reliance on, and the tendency to cling to, legacy industries such as agriculture, low tech manufacturing and low wage service sectors like tourism;

- Inferior digital infrastructure compared to the cities;

- The absence or under-performance of educational institutions not yet geared up for the new economy and often failing to recognise the threats from, and opportunities afforded by, disruption.

These challenges must be addressed in any digital economy strategy. Addressing these problems form the high-level strategic objectives of a digital strategy. Action plans and projects will follow them.

In particular, the threefold issues of access (infrastructure), affordability and capability must form the focus of a digital economy strategy.

The provision of infrastructure that is broadly accessible to the whole population and the skill building work that is required to take advantage of the new connectivity that exists will be critical to enhancing the capacity of regions to survive and prosper.

Many regions now have digital strategies. Those that do not will be severely disadvantaged in the emerging global economy.

Those regions with digital strategies must prioritise them over most other economic development activities, in particular the attraction of old economy businesses (such as call centres), and shift their focus towards capacity building for business and the community.

Regions which do not currently have a digital strategy should acquire one without delay.

A digital economy action plan

The deficits commonly experienced in regions and alluded to above must become targets for early activity in any digital action plan.

First, the pull of chunky, traditional industry sectors which might provide many jobs and contribute high value and exports to the local economy is often strong and takes the attention of economic development agents and agencies. This pull must be broken, because large sectors do not necessarily provide the growth opportunities of the future, and all economic development activity must be future-facing.

Second, the education sector must be harnessed to provide basic and advanced skills training for business owners, start-ups, emerging entrepreneurs and the young in general. Educational institutions are often not part of the economic development furniture, and this needs to change.

Third, there is an ongoing advocacy task for local authorities to ensure that central government and private sector providers of digital infrastructure are on-message in relation to the provision of adequate and affordable hardware for businesses and communities. Given that technology itself is forever taking new turns – witnessed in the recent emergence of the internet of things, big data, machine learning and so on, a strategy will need to be agile and focused upon the next things that will enhance business capacity and opportunity, not just catch-up.

Fourth, the attraction of industry to regions must become the attraction of entrepreneurs involved in technology industries and digitally skilled talent. The things that will attract these people, highly by Richard Florida (2002) and others, include both lifestyle and business culture elements. Now they will demand strong local entrepreneurship ecosystems, a term not even current when Florida first began examining the drivers of skills migrant and talent location.

Fifth, the focus of local authorities and economic development practitioners must shift to network development. Agencies can be either funders, connectors, supporters or organisers of entrepreneurship ecosystems. While ecosystem development must be led by entrepreneurs, often in regions which lack any form of a visible, active network of technology companies and start-ups there is foundational work to be done in driving early progress in the development of such ecosystems, ahead of the entrepreneurs themselves.

Sixth, there is room, indeed the necessity, for agencies to work with individual businesses and clusters of businesses to improve their digital exposure and capability. This is needed across all sectors, especially sectors in regional economies with poor progress towards digital maturity (say, retail in many regions) and will involve the funding agencies providing increased support to those business coaches, mentors and advisers who are already working with regional businesses. There will always be early adopters and stragglers in any sector or region, and agencies will need to determine where their local economy’s strategic priorities lie.

Many regional economic development strategies are delivered through distributed implementation models, since economic development is a “team sport” across many agencies, funders and stakeholders.

This is the case even where there is a designated economic development agency (EDA or RDA).

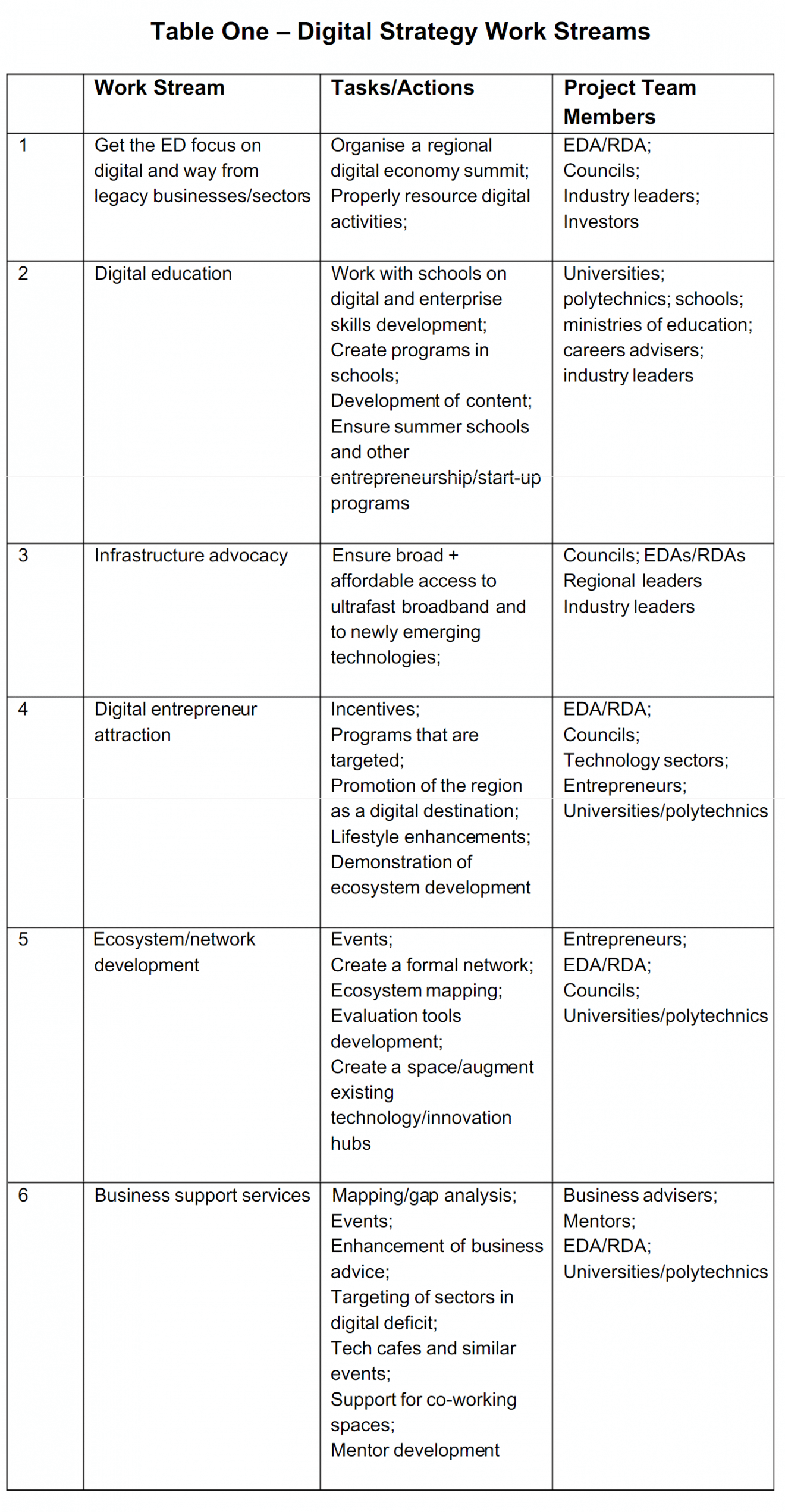

Table One sets out elements of a regional digital economy strategy, with key tasks and project partners.

Tasks will need to be developed into specific action items and the following elements will ensure effective strategy implementation:

- Clearly articulated vision, objectives and detailed action plan;

- All actions to be determined only following a landscape scan/mapping/gap analysis of existing activity;

- An evaluation framework;

- A funding model for ensuring that actions are implemented;

- A communications and engagement plan;

- Protocols for agencies to collaborate;

- Protocols for agencies to contribute in-kind resources to strategy work;

- Protocols for distinguishing the day-to-day ongoing work of agencies from new, strategic actions;

- A reporting mechanism.

Appendix A provides a primer for project teams and project leads engaged in regional economic development strategy implementation, and augments the processes set out in this paper

All this economic development strategy work should take place according to the lean canvas/lean start- up approach, through ideation, the development of a minimal viable product, fail fast, learn, pivot where necessary, iterate (Ries 2011; Feld 2012; Blank 2013; Maurya 2016).

In other words, policy and strategic initiatives should involve key entrepreneurs but should be led by a regional team of economic development practitioners with access to existing networks and funding sources.

These teams should be given proper resources and the freedom to try experiments in ecosystem development. They should have sufficient resources for these tasks. They should be provided with a space in which to focus on ecosystem development efforts. They should contain technology expertise and business expertise. They should create “happy noise” around their efforts, especially through events, speakers and the parading of expertise.

Summing up

Digital strategy is essential for economic development agents and agencies in the era of the knowledge economy and the era of business model disruption.

Economies are increasingly being driven by platformed businesses operating globally and creating the bulk of the regional jobs now created.

Digital strategies must address the three core elements where provincial regions typically suffer deficits in relation to urban regions – adequate infrastructure, affordability for business and households, and capacity to gain from the digital economy.

It is only where all three issues are addressed that regions will avoid the risks of the digital economy and leverage its benefits. And the benefits are considerable in terms of living standards and skills development.

Six workstreams are required in order to advance the position of regions and their businesses and communities. And strategic action must always be collaborative, differentiate between new strategic work and existing programs and structures, and ensure that all relevant stakeholders are brought into the project teams that will drive strategy implementation in the modern distributed networks that populate our regions.

Appendix one – A primer for economic development strategy project teams

The role of project teams is critical to the success of a collaborative, distributed and, typically, funding-constrained overarching regional development strategy.

The task for project teams will be complex, however, as:

- Many existing organisations across regions already engage in activities now articulated as actions in the regional strategy, either in siloes or collaboratively;

- There may not have been an audit of all the activities currently undertaken across the broad sweep of Strategy actions, nor conclusions drawn as to how existing activities by agencies might constrain strategy project teams;

- The distinction between agencies’ “business as usual” actions and new, collaborative strategy work is blurred and not yet subject to agreement among stakeholders;

- Agencies’ BAU activities are not always transparent and known to strategy project teams;

- Project teams are not necessarily aware of the work of other project teams whose work may overlap with their own;

- Absent clear funding principles, variable resourcing of strategy project teams by stakeholder agencies and the lack of agreement to date among agencies about in-kind contributions to collaborative activity, the progress of project teams has been uneven;

- Individual funding opportunities continue to be pursued across strategy actions in an uncoordinated way;

- ED strategy may contain elements of social development/inclusion, hence there will be some duplication/overlap to be managed with BAU social development actions.

All this means that it is up to project teams to develop their own solutions to the complexity in order to make progress on individual actions while funding remains unclear and until any governance uncertainty is resolved.

Workshops for project teams

It is generally advisable that a series of workshops be held in order to prepare project leads and project teams for a more integrated approach to delivery.

This article is a resource for project teams to make better sense of their tasks at this early stage, and to prompt questions and discussion about how better to support project teams and project leads during the early stages of regional strategy delivery.

Earlier work by agencies involved in regional strategy development gain an understanding of which agencies should be involved in project teams. This explains the assignment of tasks to agencies outlined in the linked strategy document.

However, in view of the uncertainties surrounding strategy delivery, it is important to set out clearly how a distributed, collaborative model is intended to proceed, and to provide relevant context and advice to all involved in project teams.

Key early tasks of stakeholder agencies and project teams

Stakeholder agencies will need to ensure that they understand their commitments to implementing the overall strategy and that they are resourced to help deliver on actions.

The capacity of agencies to do this will vary, and the governance team will need to work with agencies to ensure the smooth delivery of agreed projects.

Absent a funding model, this will include both monetary and in-kind contributions.

Agencies – not all of which have been closely involved in the development of the regional strategy – will need to be informed of the expectations of the region related to delivery, and to have a clear sense of how collaborative strategy actions impact, and are impacted by, their own BAU activities.

Important early tasks for designated project leads and teams are likely to include:

- Develop a clear understanding of the intent of the strategic action to which they are assigned;

- Have a broad understanding of how their action(s) link to other actions in the strategy;

- Determine with the strategy Project Manager the priority currently accorded to their project(s);

- Determine protocols for collaboration in the team;

- Conduct a scan of the landscape surrounding their project(s) – who is already playing in the area, what the gaps are, what central Government may be doing/funding or intending to do/fund, what the strategic opportunities are for new activity;

- Select other project team members, if these have not been fully articulated in the strategy action plan or where this needs to change;

- Include where appropriate representation from the private and non-government organisation sectors;

- Ensure appropriate representation from core strategic partners on project teams;

- Ensure there is expertise related to the proposed strategy action on each team;

- Bring project team members together for a planning session;

- Engage with stakeholders who have an interest in the action(s);

- Determine project timelines and evaluation frameworks for the action(s);

- Keep the reporting/monitoring system up-to-date for their action(s);

- Advise the strategy communications consultant of progress, milestones and opportunities for providing information to the community; and

- Indicate an end date for their project work.

Project teams should meet regularly and project leads should seek out and contact other project leads working on cognate action plans.

It is likely that project teams will find many different things when they undertake their initial stocktakes of existing regional activity.

Some areas will have a raft of existing activity, undertaken, either singly by agencies in isolation or collaboratively with others.

Other action teams may find isolated good work that might be scaled regionally or act as pilots for broader strategy development. Some action teams may find they have little new to do, since progress might already be being made through BAU work by agencies.

Other teams might find that precious little is currently being done in areas that demand a coherent, strategic regional approach. Some teams might find great things happening, but from which groups in the community are excluded.

Other teams might find good things being done but that need to be accorded higher regional priority and extra funding.

Project teams might find that they need to make strategic recommendations to the governance group such that a strategic action should become the BAU work of a particular agency.

It is important that project teams remember that the strategy is a regional strategy made up of regional (cross local council boundaries) actions, that it is a partnered strategy, and that it seeks that agencies work “differently” from the past in order to achieve better regional outcomes.

About the Author

Paul Collits is a strategist, civic entrepreneur, writer, university lecturer, independent researcher, policy adviser, business mentor and ideas gardener working at the intersection of business support and economic development. He has in regional economic development analysis, research, training, policy and practice for over 25 years – in universities, government, councils and regional organisations, in Australia and New Zealand. He holds BA (Hons) and Master’s degrees in political science from the Australian National University and a PhD in geography and planning from the University of New England, Australia.

References

Blank S (2013) The Four Steps to the Epiphany, K&S Ranch

Bond S (2015) Personal correspondence

Brynjolfsson E and McAfee A (2014) The Second Machine Age: Work Progress and Prosperity in a time of Brilliant Technologies, 2014

Bukht R and Heeks R (2017) Defining, Conceptualising and Measuring the Digital Economy, Development Informatics Working Paper Series, UK Economic and Social Research Council https://diodeweb.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/diwkppr68-diode.pdf

Collits P (2017a) Building an Entrepreneurship Ecosystem – the Who, the Why and the How, Paper delivered at the EDNZ Conference, Wellington, September

Collits P (2017b) Innovation, Business Transformation, the New Economy and Economic Development, Lecture at EIT, September

Ries E (2011) The Lean Startup, Penguin Books

Florida R (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class, and How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, Basic Books

Kilpi E (undated) “The Future of Firms – Is There an App for That?”

Kilpi E (undated) “Are Markets the Future of Firms?”

Mason C and Brown R (2013) Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship, OECD

Maurya A (2016) Scaling Lean: Mastering the Key Metrics for Startup Growth, Portfolio Penguin

Miles M and Morrison M (2016) The Elements of Entrepreneurship Ecosystems in Regional Areas and Options for Their Development, paper delivered at the SEGRA Conference, Albany

Romer P (1986) “Increasing Returns and Long Run Growth”, The Journal of Political Economy, Vol 94 No 5

Tapscott D (2015) The Digital Economy: Rethinking Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence, McGraw Hill Education