Let’s say you’re interviewing a new applicant for a job and you feel something is off.

You can’t quite put your finger on it, but you’re a bit uncomfortable with this person.

They say all the right things; their resume is excellent, they’d be a perfect hire for this job — except your gut tells you otherwise.

Should you go with your gut?

In such situations, your default reaction should be to be suspicious of your gut.

Research shows that job candidate interviews are poor indicators of future job performance.

Unfortunately, most people tend to trust their gut over their head and give jobs to people they like and perceive as part of their in-group, rather than merely the most qualified applicant.

In other situations, however, it does make sense to rely on gut instinct to make a decision.

Yet research on decision-making shows that most people don’t know when to rely on their gut and when not to do so.

The reactions of our gut are rooted in the more primitive, emotional and intuitive part of our brains that ensured survival in our ancestral environment.

Why was it important for people to trust their gut instincts in the past?

Tribal loyalty and immediate recognition of friend or foe were especially useful for thriving in that environment.

In modern society, however, our survival is much less at risk.

Our gut is more likely to compel us to focus on the wrong information to make decisions in the workplace and other areas.

For example, is the job candidate mentioned above similar to you in race, gender, socioeconomic background?

Even seemingly minor things like clothing choices, speaking style and gesturing can make a big difference in determining how you evaluate another person.

Our brains tend to fall for the dangerous judgment error known as the “halo effect,” which causes some characteristics we like and identify with to cast a positive “halo” on the rest of the person. It’s opposite the “horns effect,” in which one or two negative traits change how we view the whole.

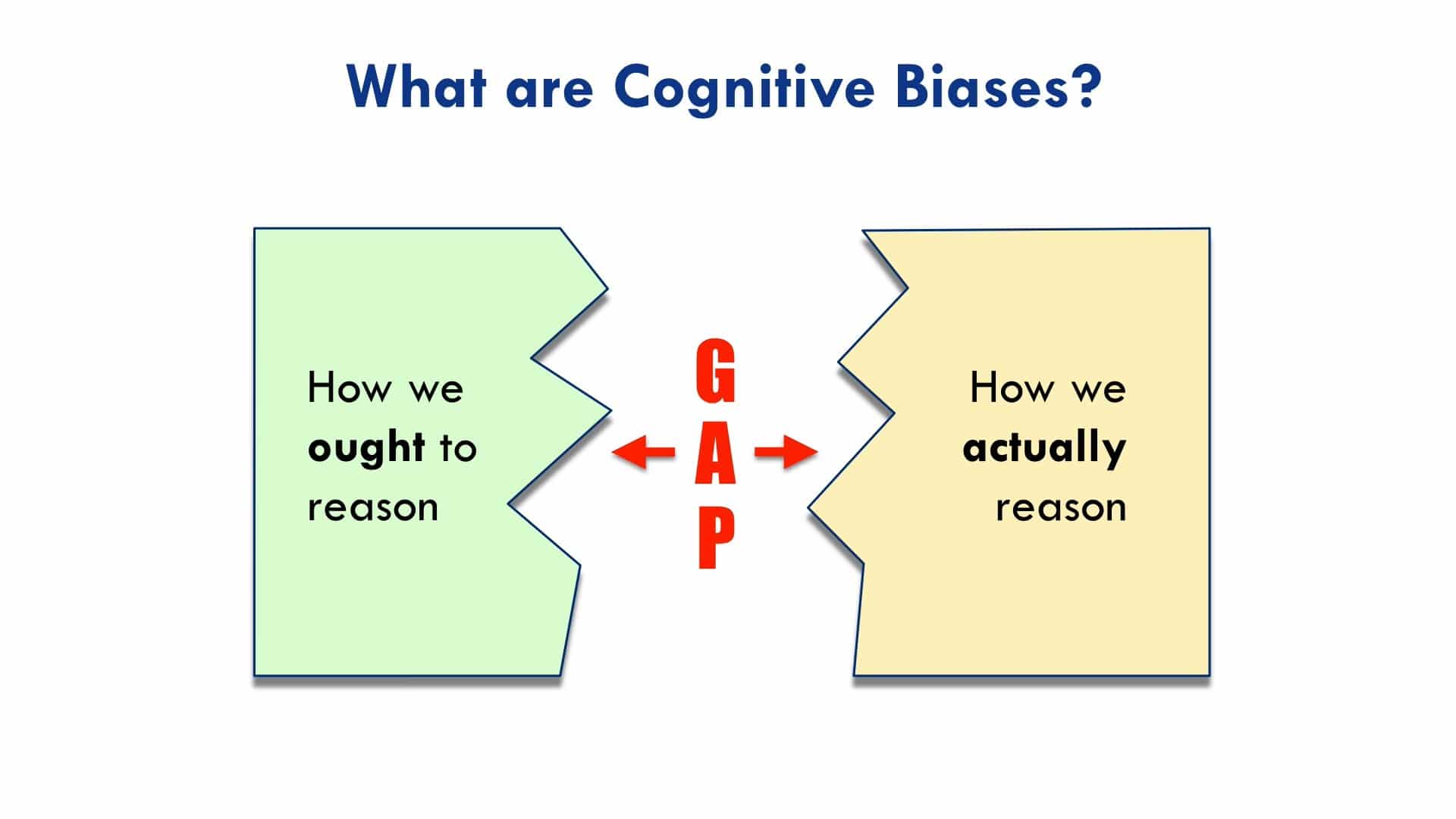

The halo effect and horns effect are two of many dangerous judgment errors, which are mental blind spots resulting from how our brain is wired that scholars in cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics call cognitive biases.

Understanding cognitive biases

Fortunately, recent research in these fields shows how you can use pragmatic strategies to address these dangerous judgment errors, whether in your professional life, your relationships, or other life areas.

You need to evaluate where cognitive biases are hurting you and others in your team and organization.

Then, you can use structured decision-making methods to make “good enough” daily decisions quickly; more thorough ones for moderately important choices; and an in-depth one for truly major choices.

Such techniques will also help you implement your decisions well, and formulate truly effective long-term strategic plans.

Besides, you can develop mental habits and skills to notice cognitive biases and prevent yourself from slipping into them.

For example, you need to remember that just because a person is similar to you does not mean she will be the best employee.

The research is detailed that our intuitions often don’t serve us well in making the best hiring decisions.

Such reliance on intuition is especially harmful to workplace diversity and paves the path to bias in hiring, including in terms of race, disability, gender and sex.

Despite the numerous studies showing that structured interventions are needed to overcome bias in hiring, unfortunately, business leaders and HR personnel tend to over-rely on unstructured interviews and other intuitive decision-making practices.

Due to our overconfidence bias, a tendency to evaluate our decision-making abilities as better than they are, leaders often go with their guts on hires and other business decisions rather than use analytical decision-making tools that have demonstrably better outcomes.

A proper fix is to note how the applicant is different from you, and give them “positive points” for it.

Alternatively, create structured interviews with a set of standardized questions asked in the same order to every applicant.

Comprehending subtle cues

Let’s take a different situation.

Say you’ve known a business colleague for many years, collaborated with her on a wide variety of projects and have an established relationship.

Imagine yourself having a conversation with her about a potential collaboration.

For some reason, you feel less comfortable than usual.

Most likely, your intuitions are picking up subtle cues about something being off.

Maybe it’s nothing.

Maybe that person is having a bad day or didn’t get enough sleep the night before.

However, that person may also be trying to pull the wool over your eyes.

When people lie, they behave in ways that are similar to other indicators of discomfort, anxiety and rejection, and it’s tough to tell what’s causing these signals.

Overall, this is an excellent time to take your gut reaction into account and be more suspicious than usual.

The gut is vital in our decision-making to help us notice when something might be amiss in well-established relationships.

Yet in most situations, when we face significant decisions about workplace relationships, we need to trust our head more than our gut to make the best decisions.