A review of the leadership literature provides one with a plethora of definitions and theories, all of which are defined or propounded to suit the perception of the authors who suggested them, or as descriptions of the leadership landscape that existed during certain eras or periods of human life.

This dynamism or unsettling nature of discourses on the concept of leadership may be attributed to the dynamic nature of the concept itself.

The construct of leadership, as a determining factor to the realization of collective goals fueled by man’s insatiable needs dictated by changes in time and also its interaction with a wide range of entities (individuals, assets and community) with different demands and behaviors must always seek to catch up to ensure its relevance, hence, its dynamic nature.

Therefore, an attempt to hazard a definition that comprehensively captures or encapsulates what leadership is about would be an exercise in futility. However, an examination of the various theories (with a greater focus on Africa and contemporary ones) that have emerged in leadership provides some foundation to its understanding and appreciation.

Older theories on leadership looked at the concept on a wide spectrum. Some of these theories personalized the concept looking at it as a role only attainable by individuals born with certain innate qualities or personal characteristics – Great Man and Trait theories.

Some also looked at it considering the behaviors or the actions exhibited by individuals in such leadership roles – Behavioral theory.

Finally, also others looked at it as a process that is context-specific. Situational and Contingency theories. However, these theories suffered several flaws as they solely focused on the role of the individual (leader) in achieving set organizational goals, neglecting the importance of the contributions of followers and the need for enhanced relationship between leaders and followers for effectiveness in goal attainment, hence, leading to the emergence of newer theories that were more ideal and effective.

Cooper and Nirenberg (2012: 1) looked at leadership effectiveness from two perspectives: one looked at the perception of leadership effectiveness from a small social group perspective, while the other looked at it from a larger social group perspective (political arena) with complex structures.

According to Cooper and Nirenberg, effective leadership within the small social group perspective would mean the successful exercise of personal influence by one or more people that result in accomplishing shared objectives in a way that is personally satisfying to those involved.

According to Cooper and Nirenberg (2012: 5):

[…] leadership effectiveness is fundamentally the practice of the following principles:

- build a collective vision, mission, and set of values that help people focus on their contributions and bring out their best;

- establish a fearless communication environment that encourages accurate and honest feedback and self-disclosure;

- make information readily available;

- establish trust, respect, and peer-based behaviour as the norm;

- be inclusive and patient, show concern for each person;

- demonstrate resourcefulness and the willingness to learn, and create an environment that stimulates extraordinary performance.

This article will focus on sustainable development in its first part. The section explains the different types of development – vertical and horizontal.

The second part discusses the methodology used to gather the information. The researcher uses a thorough literature review conducted to find and analyze which kind of leadership is needed for sustainable development from an African perspective.

The third part gives the findings of the research. A critical assessment of the African leadership landscape as captured above portrays a leadership landscape marked by every single characteristic of bad leadership.

The last part provides a framework for leadership development. With the current environment that is changing, it is becoming more complex and challenging to adapt to these new trends.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND LEADERSHIP

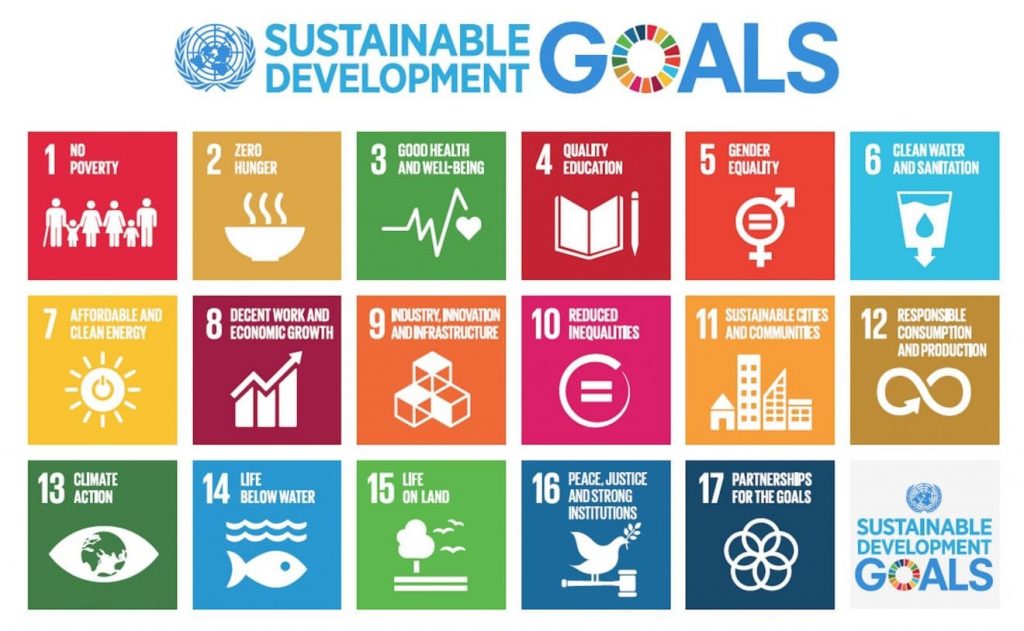

The concept of sustainable development was popularized by the World Commission on Environment and Development as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987).

However, many scholars have given several interpretations of the concept. According to Malia and Clarkson (2009), the sustainable development concept is complex and multifaceted. The various perspectives on this subject are embedded in people’s own beliefs regarding sustainable development.

No wonder sustainable development is viewed by politicians in terms of community projects; by businesses as goods and profits; by environmentalists as a means of enabling efficient use of natural resources; and by the masses as a means of meeting their needs as well as a strategy for alleviating poverty.

Sustainable development defies a single definition due to its multifaceted and multidimensional nature. Two major schools of thought, however, attempt to tackle the concept in a better perspective.

According to ecologists, sustainability literally refers to the preservation of the state and function of the ecological system.

Meanwhile, sustainability is considered as the maintenance and improvement of the lives of humans by economists.

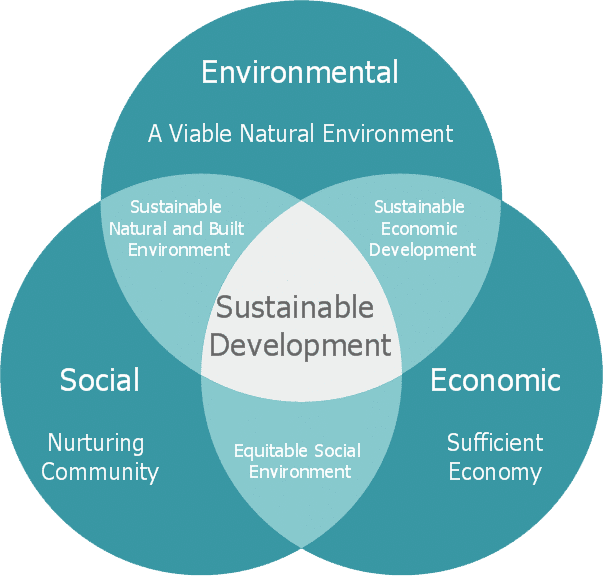

However, Mckeown (2002) proffers that the central tenet of sustainable development reveals three distinct components: environment, society, and economy that are intertwined and not separated.

Thus, achieving sustainable development requires a more balanced relationship among the environment, society, and economy in pursuit of development and improved quality of life.

Robert Solow summarizes the concept of sustainable development by suggesting that sustainability cannot be expressed by any means less than a sanction that preserves productive capacity for posterity (Solow, 1986, 1999).

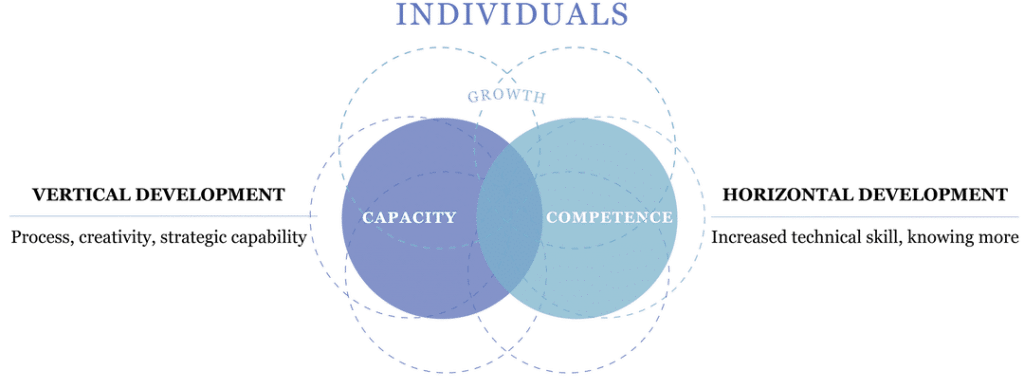

For a long time, we have thought about leadership development as working out what competencies a leader should possess and then helping individual managers to develop them – much as a bodybuilder tries to develop different muscle groups. We have failed to distinguish between two very different types of development – vertical and horizontal.

Types of Development

Horizontal development is the development of new skills, abilities, and behaviors. It is technical learning.

Horizontal development is most useful when a problem is clearly defined and there are known techniques for solving it.

Surgery training is an example of horizontal development. Students learn to become surgeons through a process known as “pimping,” in which experienced surgeons continually question students until the point when the student cannot answer and is forced to go back to the books to learn more information.

While the process of learning is not easy, there are clear answers that can be codified and transmitted from expert sources, allowing the students to broaden and deepen their surgical competency.

Vertical development, in contrast, refers to the “stages” that people progress through regarding how they “make sense” of their world.

We find it easy to notice children progressing through stages of development as they grow, but conventional wisdom assumes that adults stop developing at around 20 years old – hence the term “grown-up” (you have finished growing).

However, developmental researchers have shown that adults do continue to progress (at varying rates) through predictable stages of mental development.

At each higher level of development, adults “make sense” of the world in more complex and inclusive ways – their minds grow “bigger.”

In metaphorical terms, horizontal development is like pouring water into an empty glass. The vessel fills up with new content (you learn more leadership techniques).

In contrast, vertical development aims to expand the glass itself. Not only does the glass have increased capacity to take in more content, but the structure of the vessel itself has also been transformed (the manager’s mind grows bigger).

From a technology perspective, it is the difference between adding new software (horizontal development) or upgrading to a new computer (vertical development).

Most people are aware that continuing to add new software to an out-dated operating system starts to have diminishing returns.

While horizontal development (and competency models) will remain important as one method for helping leaders develop, in the future it cannot be relied on as the only means.

As one interviewee suggested, it is time to “transcend and include” the leadership competency mentality so that in the future we can grow our leaders simultaneously in both horizontal AND vertical directions.

Why Vertical Development Matters for Leadership

The next question may be: “Why should someone’s level of cognitive development matter for leadership and organizations?”

One answer is that from a leadership perspective, researchers have shown that people at higher levels of development perform better in more complex environments.

The literature showed that across a range of leadership measures, there was a clear correlation between higher levels of vertical development and higher levels of effectiveness.

This finding has since been replicated in several fine-grained studies on leaders assessing particular competencies. The reason that managers at higher levels of cognitive development can perform more effectively is that they can think in more complex ways.

What the Stages of Development Look Like

There are various frameworks which researchers use to measure and describe levels of cognitive development. Below is a short description of Robert Kegan’s levels of development and how they map against other researchers in the field.

Kegan’s Adult Levels of Development

- Level 3 – Socialized mind: At this level, we are shaped by the expectations of those around us. What we think and say is strongly influenced by what we think others want to hear.

- Level 4 – Self-authoring mind: We have developed our ideology or internal compass to guide us. Our sense of self is aligned with our belief system, personal code, and values. We can take stands, set limits on behalf of our own internal “voice.”

- Level 5 – Self-transforming mind: We have our ideology, but can now step back from that ideology and see it as limited or partial. We can hold more contradiction and oppositeness in our thinking and no longer feel the need to gravitate towards polarized thinking.

Adult Levels of Development

According to the literature, the coming decades will increasingly see managers take on challenges that require them to engage in: strategic thinking, collaboration, systems thinking, leading change, and having “comfort with ambiguity.”

These are all abilities, which become more pronounced at level 5. Yet according to studies by Torbert and Fisher12 less than 8% have reached that level of thinking. This may in part explain why so many people are currently feeling stressed, confused, and overwhelmed in their jobs.

A large number of the workforce are performing jobs that cause them to feel they are “in over their heads” (Kegan, 2009).

What Causes Vertical Development

The methods for horizontal development are very different from those for vertical development.

Horizontal development can be learned (from an expert), but vertical development must be earned (for yourself).

We can take what researchers have learned in the last 75 years about what causes vertical development and summarize it by the following four conditions (Kegan, 2009):

- People feel consistently frustrated by situations, dilemmas, or challenges in their lives.

- It causes them to feel the limits of their current way of thinking.

- It is in an area of their life that they care about deeply.

- There is sufficient support that enables them to persist in the face of anxiety and conflict.

Developmental movement from one stage to the next is usually driven by limitations in the current stage.

When you are confronted with increased complexity and challenge that can’t be reconciled with what you know and can do at your current level, you are pulled to take the next step (McGuire & Rhodes, 2009).

Besides, development accelerates when people can identify the assumptions that are holding them at their current level of development and test their validity.

Torbert and others have found that cognitive development can be measured and elevated not only on the individual level but also on the team and organizational level.

McGuire and Rhodes (2009) have pointed out that if organizations want to create lasting change, they must develop the leadership culture at the same time they are developing individual leaders.

Their method uses a six-phase process, which begins by elevating the senior leadership culture before targeting those managers in the middle of the organization.

While personal vertical development impacts individuals, vertical cultural development impacts organizations.

The challenge for organizations that wish to accelerate the vertical development of their leaders and cultures will be the creation of processes and experiences that embed these developmental principles into the workplace.

McGuire and Rhodes describe vertical development as a three-stage process:

- Awaken: The person becomes aware that there is a different way of making sense of the world and that doing things in a new way is possible.

- Unlearn and discern: The old assumptions are analyzed and challenged. New assumptions are tested out and experimented with as being new possibilities for one’s day-to-day work and life.

- Advance: Occurs after some practice and effort, when new ideas get stronger and start to dominate the previous ones. The new level of development (leadership logic) starts to make more sense than the old one.

Example of a Vertical Development

Process: The Immunity to Change

The “Immunity to Change” process was developed over 20 years by Harvard professors and researchers Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey.

It uses behavior change, and the discovery of what stops people from making the changes they want, to help people develop themselves.

How it works:

Leaders choose behaviors they are highly motivated to change. They then use a mapping process to identify the anxieties and assumptions they have about what would happen if they were to make those changes.

This uncovers his or her hidden “immunity to change,” i.e., what has held his or her back from making the change already.

The participant then designs and runs a series of small experiments in the workplace to test out the validity of the assumptions.

As people realize that the assumptions they have been operating under are false or at least partial, the resistance to change diminishes and the desired behavior change happens more naturally.

Why it accelerates development:

The method accelerates people’s growth because it focuses directly on the four conditions of vertical development (an area of frustration, limits of current thinking, an area of importance, and support available).

Many leadership programs operate on the assumption that if you show people how to lead, they can then do that. However, the most difficult challenges that people face in their work lives are often associated with the limitations of the way they “make meaning” at their current level of development.

When a person surfaces the assumptions they have about the way the world works, they get the chance to question those assumptions and allow themselves the opportunity to start to make meaning from a more advanced level.

For example, a manager may have difficulty making decisions without his boss’s direction, not because he lacks decision-making techniques, but because of the anxiety that taking a stand produces from his current level of meaning-making (the Socialized Mind).

How this is being used:

The method is currently being used in the leadership development programs of many leading banks, financial services firms, and strategy consulting firms. It is best suited for leaders who already have the technical skills they need to succeed, but need to grow the capacity of their thinking to lead more effectively.

Trend 1: Increased Focus on Vertical Development (Developmental Stages)

Research question:

What do you think needs to be stopped or phased out from the way leadership development is currently done?

- Competencies: they become either overwhelming in number or incredibly generic. If you have nothing in place they are okay, but their use nearly always comes to a bad end.

- Competencies – they don’t add value.

- Competency models as the sole method for developing people. It is only one aspect and their application has been done to death.

- Competencies, especially for developing senior leaders. They are probably still okay for newer managers.

- Static individual competencies. We are better to think about meta-competencies such as learning agility and self-awareness.

Trend 2: Transfer of Greater Developmental Ownership to the Individual

According to social psychologists, people’s motivation to grow is highest when they feel a sense of autonomy over their development. However, some interviewees believe that the training model common within organizations for much of the last 50 years has bred dependency, inadvertently convincing people that they are passengers in their development journey.

The language of being “sent” to a training program, or have a 360 – degree assessment “done on me,” denotes the fact that many managers still see their development as being owned by someone else, namely HR, training companies, or their manager.

Even as methods have evolved, such as performance feedback, action learning, and mentoring, the sense for many remains that it is someone else’s job to “tell me what I need to get better at and how to do it.”

Many workers unknowingly outsourced their development to well-intentioned strangers who didn’t know them, didn’t understand their specific needs and didn’t care as much about their development as they should.

This model has resulted in many people feeling like passengers.

The challenge will be to help people back into the driver’s seat for their development.

Several researchers point out that the above issue has been compounded in the last 10 years by the demand placed on managers to take on the role of coaches and talent developers.

Many staff, however, express scepticism at being developmentally coached by managers, whom they believe are not working on any development areas themselves. To paraphrase Rob Goffee’s 2006 book, “Why should anyone be developed by him?”

In an organization where everyone is trying to develop someone else, but no one is developing themselves, we might wonder whether we are approaching development from the right starting point.

Despite staff’s doubts about the current top-down development methods, we can see clues to the future of development in the growing demand for executive coaching.

What principles can be learned from this demand for coaching that can be expanded to all development practices?

Some modifying factors for coaching:

- The manager chooses what to focus on, not the coach.

- The process is customized for each person.

- The coach owns their development; the coach guides the process (through questions).

- The coach is a thinking partner, not an authority/expert.

- There is no “content” to cover.

- It is a developmental process over time, not an event.

Despite this demand for coaching, the barrier has always been that it is difficult to “scale” the process, because of the cost and time needed for the coach. However, if greater ownership of development is transferred back to the individual, with HR, external experts, and managers seen as resources and support, there is no reason that these same principles could not be applied on a larger scale throughout an organization.

While many organizations say that they need leaders at all levels of the business, several interviewees pointed out that this statement appears inconsistent with their practices, as long as they continue to train and develop only their “elite” managers.

Leadership development can become democratized if workers get a better understanding of what development is, why it matters for them, and how they can take ownership of their development.

Leadership Development for the Masses – What Development Might Look Like?

Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey (2009) suggest that you would know that an organization had people taking ownership of their ongoing development when you could walk into an organization and any person could tell you:

- What is the one thing they are working on that will require that they grow to accomplish it;

- How they are working on it;

- Who else knows and cares about it;

- Why this matters to them.

Academy of Management Executive

In addition to these points, research suggests that some of the following factors would also be present in an organization where people were taking greater ownership of their development:

- Recognition from senior leaders that in complex environments, business strategies cannot be executed without highly developed leaders (and that traditional horizontal development won’t be enough);

- Buy-in from the senior leaders that new methods for development need to be used and that they will go first and lead by example;

- Staff to be educated on the research of how development occurs and what the benefits are for them;

- For all staff to understand why development works better when they own it;

- A realignment of reward systems to emphasize both development as well as performance;

- Utilization of new technologies such as Rypple, which allows people to take control of their feedback and gather ongoing suggestions for improvement;

- Creation of a culture in which it is safe to take the type of risks required to stretch your mind into the discomfort zone.

We are already seeing examples of this happening at innovative organizations such as Google, where managers may have up to 20 direct reports each.

As top-down feedback and coaching is impractical with so many direct reports, staff members are expected to drive their development by using peers to gather their feedback on areas to improve and to coach each other on how they can develop.

Growth Fuels Growth

While many HR staff may be delighted at the possibility that, in the future, people would take more ownership for their development, some may question whether people are inherently motivated to grow.

Yet, the majority of people can reflect on what is common knowledge in most workplaces: the people who grow the most are also the ones hungriest to grow even more.

Clayton Alderfer’s Existence, Relations, Growth (ERG) model of human needs identified that the need for growth differs from the needs for physical well-being and relationships.

Alderfer found that the need for physical well-being and relationship concerns are satiated when met (the more we get, the less we want), whereas the need for growth is not (the more growth we get, the more we want).

The implication for development is that if we can help people to get started on the path of genuine vertical development, the drive for still more growth gathers momentum.

Also, social psychologists have long identified that a sense of autonomy (ownership) is crucial for people to feel intrinsically motivated.

If the experience of development is combined with a sense of autonomy over the development process, individuals are likely to gain a significant boost in their motivation to proceed.

Finally, both Kegan and Torbert’s research suggests that as more people transition from the levels of the socialized mind to the self-authoring mind, there will naturally be a greater drive for ownership by individuals.

Of course, not everything can be organized and carried out by the individuals, and the role of learning and development professionals within organizations will remain crucial. However, it may transform into more of a development partner whose main role is to innovate new structures and processes for development.

Example of a development process that increases ownership:

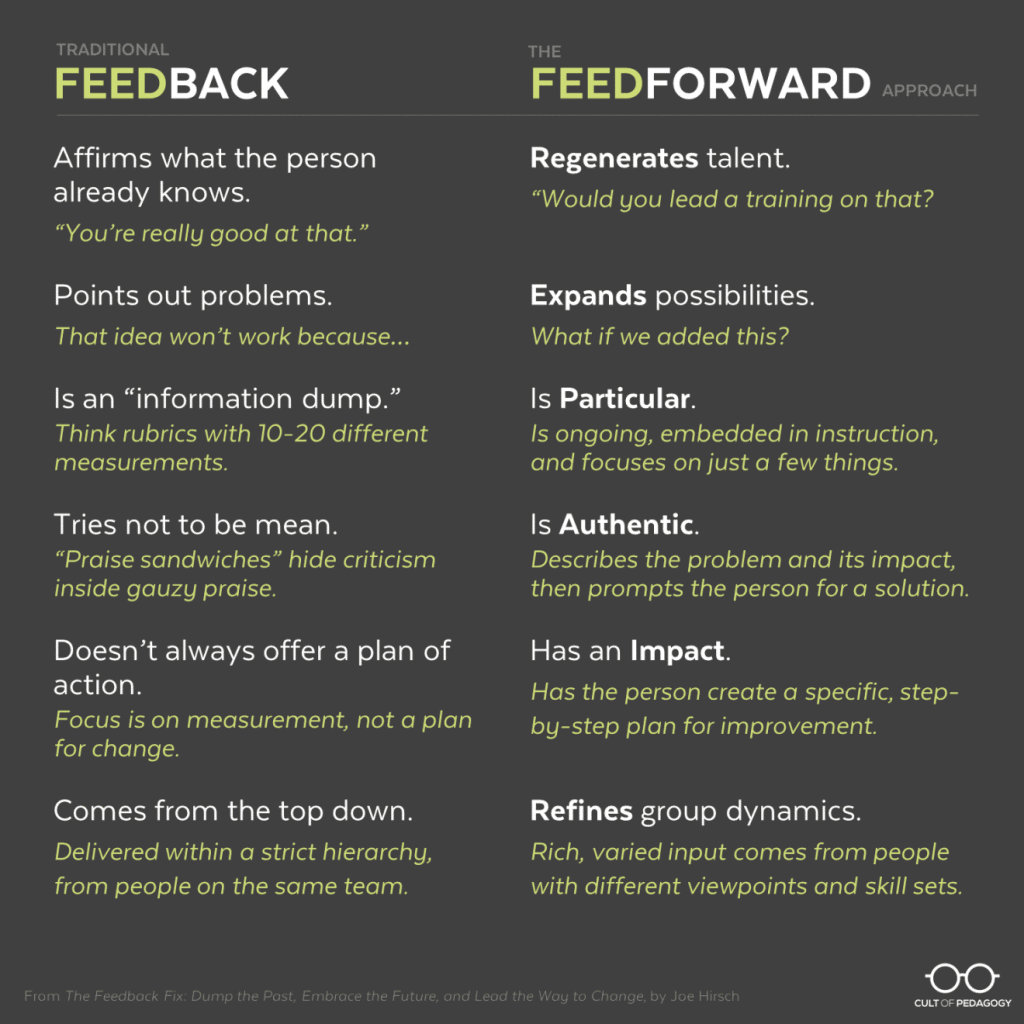

Feed-forward coaching

What is it: A behavior change process designed for busy, time-poor people who like to see measured results?

In the feed-forward process, an individual engages trusted colleagues in a peer coaching process, asking each colleague to do three things: focus on the future, give only suggestions, and make these something positive the person can do.

(Image Source: Cult of Pedagogy)

Why it works for development:

It is extremely time-efficient, taking only two to three hours per month, involves the people who know the leader best to help him/her change, measures results, holds the coaches accountable over time and acknowledges that behavior change is a process, not an event.

Feed-forward puts responsibility for development into the hands of individuals, then lets them tailor the process as to who will be involved, what they will work on, and how conversations will take place.

Also, the structure of the process ensures continuous support and accountability conversations with a coach, which helps people to keep following through on their actions.

Trend 3: The decline of the heroic leader – the rise of collective leadership

The story of the last 50 years of leadership development has been the story of the individual.

It began with discoveries about “what” made a good leader and was followed by the development of practices that helped a generation of individuals move closer to that ideal.

The workplace context rewarded individuals who could think through a situation analytically and then direct others to carry out well-thought-through procedures.

Leadership was not easy, but the process itself was comparatively clear. However, in the last 15 years, this model has become less effective, as the “fit” between the challenges of the environment and the ability of the heroic individuals to solve them has started to diverge.

The complexity of the new environment increasingly presents what Ronald Heifetz calls “adaptive challenges” in which no one individual can know the solution or even define the problem (the issue of regional decentralization for example in Cameroon that needs a broad-based dialogue to find solutions).

Instead, adaptive challenges call for collaboration between various stakeholders who each hold a different aspect of the reality and many of whom must themselves adapt and grow if the problem is to be solved.

These collectives, who often cross geographies, reporting lines, and organizations, need to collaboratively share information, create plans, influence each other, and make decisions.

A simple inference for those in charge of leadership development could be that we need to start teaching managers a new range of competencies that focus on collaboration and influence skills.

However, several interviewees suggest that something more significant may be happening – the end of an era, dominated by individual leaders, and the beginning of another, which embraces networks of leadership.

The field of innovation has already begun this process.

Andrew Hargadon, who has researched how innovations occur in organizations, says that until recently it was common to think that innovations came from lone geniuses who had “eureka” moments.

However, in the last 10 years, contrary to this “great man” theory, researchers have shown that innovation is a result of large numbers of connection points in a network that causes existing ideas to be combined in new ways.

Researchers now say that innovation doesn’t emanate from individual people; it “lives” in the social network.

Similarly, the field of leadership has long held up heroic individuals as examples of great leaders who could command and inspire organizations.

This idea resonated with the public, as well as business audiences who sought to glean leadership secrets from these leaders’ books and speeches. However, a future made up of complex, chaotic environments is less suited to the problem solving of lone, decisive authority figures than it is to the distributed efforts of smart, flexible leadership networks.

This transition in thinking may not come quickly or easily. This was evident in the media’s efforts to find the “leader” of the movement that toppled Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.

Many people were interviewed by the media without it ever becoming clear who was directing the movement.

In contrast, the youths who utilized social networking tools to force regime change after 30 years seemed clear that for them leadership was not aggregated in an individual (they didn’t have “a” leader), leadership was distributed throughout their network.

This was not the first generation of youths to be frustrated with Mubarak and want him ousted, but it was the first with the tools and the collective mindset to make it happen.

The younger generation’s comfort with social networking as the preferred means of connecting and influencing each other suggests that they will have little difficulty in accepting that leadership can be distributed throughout a network. But how quickly will others take on this thinking?

Redefining Leadership

A starting point for organizations may come from helping their people redefine what is meant by the term leadership.

There has been a major trend among organizational theorists to shift the focus from leadership as a person or role to leadership as a process

For example:

- the process of mobilizing people to face difficult challenges (Heifetz, 1994);

- anyone and everyone who gets in place and helps keep in place the five performance conditions needed for effective group functioning (Hackman, 2002);

- “Leaders are any people in the organization actively involved in the process of producing direction, alignment, and commitment.” (McCauley & Van Velsor, 2004).

A key distinction in the definitions at left is that leadership can be enacted by anyone; it is not tied to a position of authority in the hierarchy.

Heifetz believes it is far easier to exercise leadership from a position outside of authority, without the constraints that authority brings.

More importantly, these definitions do not tie the act of leadership to an individual. Leadership becomes free to be distributed throughout networks of people and across boundaries and geographies.

Who is the leader becomes less important than what is needed in the system and how we can produce it.

If leadership is thought of as a shared process, rather than an individual skillset, senior executives must consider the best way to help leadership flourish in their organizations.

Leadership spread throughout a network of people is more likely to flourish when certain “conditions” support it, including:

- open flows of information;

- flexible hierarchies;

- distributed resources;

- distributed decision-making;

- loosening of centralized controls.

Organizations that choose to embrace these conditions will align themselves with the wave of new technologies that are changing the way we work and organize our workplaces.

Grady McGonagill and Tina Doerffer (2011) suggest three stages of technological innovation that have already occurred:

- Web 1.0 (1991-2000) in which tools for faster, cheaper, and more convenient forms of communication (such as email) became available and widely used;

- Web 2.0 (2001-2010) in which use of another set of new tools for communication (such as wikis and blogs) began enabling interaction and communication in transformative ways;

- Web 3.0 (2011-present) in which powerful new computing platforms (the Cloud), a second generation of search tools, and meta-level methods for managing knowledge (such as tags and folksonomies) are beginning to realize the web’s potential to generate more immediately and personally useful knowledge from archived information.

While we are still in the early stages of thinking about leadership development at a collective level, it seems increasingly likely that future generations will see leadership residing within networks as a natural phenomenon.

With the Internet and social networking flattening hierarchies and decentralizing control, leadership will be happening throughout the system, so development methods will have to follow it there, sooner rather than later.

How Might Leadership Look Different in a Network?

For organizations to become more effective at using networks of leadership, interviewees suggested some changes that would need to occur.

First, at the collective level, the goal of an organization would be to create smart leadership networks, which can coalesce and disband in response to various organizational challenges.

These networks might contain people from different geographies, functions, and specializations, both within and external to the organization.

Just as brains become “smarter” as the number of neural networks and connections are increased, organizations that connect more parts of their social system and build a culture of shared leadership will have greater adaptability and collective capacity.

Second, organizations would use their leadership development programs to help people understand that leadership is not contained in job roles but in the process that takes place across a network of people to continuously clarify direction, establish alignment, and garner commitment (DAC) of stakeholders.

While leadership may sometimes be enacted by an individual, increasingly it will be a process that happens at the group level, with various people’s contributions influencing the DAC of the collective.

As these changes happen, the distinction between who is a leader and who is a follower becomes less clear or relevant; everyone will be both at different times.

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2010), in their comprehensive study of leadership development best practices, suggested that in the future, organizations could choose to invest their leadership development efforts to improve capacity at one of five different levels:

- individual capacity;

- team capacity;

- organizational capacity;

- network capacity;

- systems capacity.

Depending on the area in which increased capacity is desired, organizations will target different group sizes and use different development practices.

Not all types of organizations will need to adopt this new paradigm of thinking.

Traditional companies, in stable environments requiring little creativity from staff, may well be more effective if they stick to traditional, individualistic command and control management styles. However, organizations that expect to operate in VUCA environments will quickly need to develop the types of networks and cultures in which leadership flows through the system.

Complex environments will reward flexible and responsive, collective leadership, and the time is fast approaching for organizations to redress the imbalance that has been created by focusing exclusively on the individual leadership model.

Trend 4: A new era of innovation in leadership development

If at least some of the changes mentioned in the preceding sections do transpire, there are no existing models or programs, which are capable of producing the levels of leadership capacity needed.

While it will be easy for organizations to repeat the leadership practices that they have traditionally used, this continuation makes little sense if those methods were created to solve the problems of 10 years ago.

Instead, an era of innovation will be required. The creation of new development methods will be a process of punctuated progress.

Transformations are most likely to begin with small pockets of innovators within organizations, who sense that change is either needed or inevitable.

These innovators will need to be prepared to experiment and fail to gain more feedback from which to build their next iterations.

L&D innovators will need to look to find partners within and outside of their organizations who they can join with to create prototypes that push the boundaries of the existing practices.

At CCL, Chuck Palus and John McGuire are partnering with senior leadership teams to build “leadership cultures” rather than individual leader programs.

Leadership teams engage in practices to elevate their levels of development, thus creating “headroom” for the rest of the culture.

Meanwhile, David Altman and Lyndon Rego are spreading leadership capacity throughout the system by taking CCL knowledge to the “base of the pyramid” and delivering programs on the sidewalks and in villages in Africa, Asia, and India.

Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey are sharing their Immunity to Change process with universities, businesses, and school staff around the world.

Rather than try to do it all themselves, they are equipping consultants, HR practitioners, and students to take their work out into their communities.

Lisa Lahey comments, “We don’t expect to do it all, we are just two people.”

DUSUP, a Middle East oil producer, has changed its leadership programs from “content events” to “development processes” in which managers take ownership of their development.

All senior managers engaged in a six-month process in which they learned the principles of development, then put those principles into practice on themselves.

Only after they have had experience developing themselves with the new tools do they start coaching their team members to also apply them.

In the future, innovative leadership development networks will need to increase the number of perspectives that they bring together, by crossing outside of the boundaries of the leadership development community and engaging other stakeholders to help come up with transformative innovations.

Conferences that bring leadership development people together may in time give way to virtual networks facilitated by Organizational Development practitioners, which connect diverse groups of people who all have a stake in the process: executives, supervisors, customers, suppliers, as well as leadership development specialists.

This would require a different skill set for many learning and development specialists who must transfer from creating the programs for the executives to becoming the social facilitators of a construction process that involves all of the stakeholders in the system.

Given this, the greatest challenge for the L&D community may be the ability to manage the network of social connections, so that the maximum number of perspectives can be brought together and integrated.

The great breakthrough for the transformation of leadership development may turn out not to be the practices that are created but the social networking process that is developed to continuously present new practices to be distributed throughout the network.

All of these are early attempts to address the principles suggested in this article:

- Build more collective, rather than individual, leadership in the network;

- Focus on vertical development, not just horizontal;

- Transfer greater ownership of development back to the people.

These examples are not “answers” to the development challenges facing the African continent but examples of innovations.

Even greater innovative breakthroughs in the future may come from networks of people who can bring together and recombine different ideas and concepts from diverse domains.

While leadership development communities currently exist with this aim, many limit their capacity for innovation by being excessively homogeneous, with most members exclusively HR-related and of a similar generation and cultural background.

This limits the effectiveness of these collectives, both in terms of the similarity of the ideas they bring as well the implementation of those ideas, which may fail to take into account the different values and priorities of stakeholders who will have to engage in any new practices.

METHODOLOGY

A thorough literature review was conducted to find and analyze which kind of leadership is needed for sustainable development from an African perspective.

The search found for example that the constructs that affect sustainable development among Village Development and Security Committee members in Africa.

The analysis of the case revealed that leadership was perceived as imperative in promoting sustainable development by the rural community leaders.

The search identified that effective leadership helped the villages to develop in times of peril the capacity to overcome the social and community challenges that confronted them and granted them the ability to meet the needs of the people.

This points to the fact that it is important for leaders to be visionary and have a wider perspective of issues that confront them beyond their immediate environment to satisfy the tenets of sustainable development.

This attitude grants leaders an edge to conquer the challenges and problems of current times while having the ability to implement decisions that are timely, complete and responsive.

The search also revealed that the absence of good leadership could lead to situations where activities in the villages would stagnate and move out of order.

This construct could be supported by the need for management control in organizations that shapes individual behaviors, coordinates resources, both human and material and directs the efforts of the individual workers toward the achievement of the organizational goals.

This helps to produce maximum benefit and helps in the growth and survival of the organization. The same could be said of effective leadership if it is replicated at the national level.

Effective leadership has the propensity to coordinate the resources of a country to promote sustainable development.

Similarly, Perren and Burgoyne (2001) identified a set of key management and leadership abilities from a study that was conducted by the Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership on leadership qualities that impact upon sustainable development.

From the study, eight meta-groups of three generic categories were deduced from 83 distinct management and leadership abilities that were identified. These three categories and groups were as follows:

- Thinking abilities: the ability to think strategically.

- People abilities: self-management, managing and leading people, direction and culture, managing relationships.

- Task abilities: managing information, managing resources, managing activities, and quality.

From the findings of the above study, it is evident that peculiar leadership skills are required for sustainable development to be realized in any setting Africa included.

These skills and abilities involve a leader’s ability to be visionary, have control over people and also manage tasks in a way that ensures efficiency and effectiveness.

Leadership experienced in post-independence Africa, however, has manifested several instances of incompetence, ineffectiveness, and unresponsiveness to the needs of present and even future generations.

To gain full insight into the issue, there is the need to comprehensively look or assess the leadership landscape in Africa pointing out those elements that pose restrictions to its effectiveness.

African leadership landscape

According to Nasir (2010), there have been several anomalies under the stewardship of post-independence African leaders. In his view, infrastructural development in many African countries has fallen into disrepair and currencies have grossly depreciated amid high costs of living compounded with unemployment, poor healthcare, falling educational standards and lower life expectancies.

Given this, Nasir argues that ordinary life has been put under pressure coupled with the deterioration in general security, increased crime and corruption and the diversion of public funds into sanctioned ethnic discrimination.

A World Bank report blamed Africa’s underdevelopment and devastation on “the crisis of government” (Alemazung, 2011). This is supported by statistics on how leaders left office in Africa over the past four decades through coups d’état or invasions and elections (Arthur, 2000).

Again, Barka and Ncube (2012) held that the low or negative per capita gross domestic product (GDP) growth of certain Sub-Saharan African countries, as independence was as a result of their experience of more military coups than countries that had higher per capita GDP growth rates.

In addition to the above, many scholars have opined that the culture of Africa is also responsible for the leadership practices experienced on the continent (Leonard, 1987; Jackson, 2004; Bolden and Kirk, 2009).

For instance, Leonard (1987) asserts that the differences between organizational behaviour in the continent and the West are as a result of fundamental distinctions in leadership thinking and not merely managerial failures.

According to Kuada (1994), the leadership thinking in Africa is more of the sovereign-subject approach, where leadership poses high restrictions on the ability of followers to be creative and independent in thinking – quite contrary to what pertains in the West.

Kuada argues that the principal function of the loyal employee in Africa is to serve as a buffer for the immediate superior. For this reason, such a loyal subordinate is expected to do all he or she can to blame others, not excluding himself, to protect the image of his or her boss.

A similar situation occurs where employees share mutual concerns but pretend they know nothing about the situation at hand and so conceal errors.

Argyris (1990, 1993) has described such defensive behaviors as “skilled incompetence”.

According to Alemazung (2011), all societies in the world require positive development in terms of socio-economic and politico-cultural dimensions of their countries.

In societies where people live in freedom and prosperity, leaders of such societies broadly give priority to issues upon which the common good of their people depends, resulting often in a further developed and even freer people.

Leaders in such societies often serve their people by working hard to place national interests above their interests being mindful that the huge price they pay for projecting their interests above that of their people, even to the extent of losing the opportunity to serve their people.

Alemazung further opines that political development in Africa has been influenced and characterized by flaws most often in the form of attitudes of political actors, which over time have become frequent and peculiar to the continent.

In its extreme, these trends in leadership flaws have become part of the political culture of the African system. Even though these weaknesses are common beyond African systems, the dimension in which they manifest themselves in Africa and the impact they have on the socio-economic and political evolution is not only peculiar but deplorable for the continent.

FINDINGS

A critical assessment of the African leadership landscape as captured above portrays a leadership landscape marked by every single characteristic of bad leadership.

The leadership landscape of Africa paints the picture of one that is struggling to meet the needs of the present, let alone those of the future.

The idea of sustainable development looks at sustainability from three development dimensions – economic, social and environmental

with two-time frames – the present and the future.

It advocates the balancing of these three dimensions to ensure the sustenance of the human race presently and in the future.

Because of this, there has been a clarion call at both national and international levels for a change in consumption and production patterns to ensure the availability of resources for future consumption and production.

To achieve this, leadership at both national and organizational levels would have to adopt leadership styles that engenders a sense of shared responsibility toward the attainment of this goal;

- one that is focused on the long-term, and thus would establish systems that would persistently ensure the pursuance of this goal in the future;

- one that understands the need for collective effort (at both national and organizational levels) toward the attainment of the sustainability goal;

- one that is willing to learn; and, finally, one that is in itself ethical, and thus would impress upon followers the need to behave in a like manner.

This is because the sustainable development agenda is one that requires an all-hands-on-deck approach by way of a collective leadership approach between players in the industry (including civil society groups) and government.

However, as can be gathered from the African leadership landscape presented above, it is evident that leadership in Africa lacks this approach to governance or leadership.

This situation thus shrouds the possibility of Africa attaining sustainable development.

Thus, for African leaders, in both industry and government (especially government), to succeed in forging-on toward the attainment of such a goal, they would have to conduct themselves in a responsible, transparent and accountable fashion as captured under the concept of good governance.

Post-Independence African Leadership Flaws

These leadership flaws according to Alemazung can be categorized into unconstitutional leadership behaviors, unaccountable political leadership, and weak multicultural political systems.

Unconstitutional leadership behaviors

Alemazung raised several leadership issues that border on disregard for the respective constitutional provisions by some political African leaders.

According to him, the seizure of power and rule by oppression are both common phenomena in Africa that greatly influence political developments on the continent, especially the transition to democracy.

Wangomeby (1985) described the 1960s as the “decade of coups in Africa”. The majority of coups during this period involved military takeover, and by 1975, an estimated half of all countries on the continent had military or civil-military-led governments.

Election, as the mechanism to select rulers, was greatly undermined and “disqualified” in unitary/centralized states of post-independent Africa.

Within the period 1960-1970, more than 20 coups were conducted in Africa.

Examples found in the 1960s coup decade include the following:

In Togo, Etienne Eyadema killed President Silvanus Olympic in 1963 and later in 1967, took over and stayed in power through a repressive and tyrannical rule until his death in 2005 (Meredith, 2005); in Congo-Brazzaville, the government of Abbe’ Youlou was overthrown in August 1963; in Dahomey, Colonel Christophe Soghlo overthrew President Maga in December 1963; again, the overthrow of President David Dacko of Central Africa Republic in January 1966 and that of President Kwame Nkrumah by General Ankrah in February 1966 are just a few of the total number of coups in the continent.

Indeed, in Malawi, the president, Kamuzu Banda bluntly made a statement to the effect that he was ready to detain up to ten thousand or one hundred thousand to maintain political stability and efficient administration in the country (Meredith, 2005).

Unfortunately for Africa, these leaders neither ensure political stability nor do they run efficient administrations as a result of greed and love for power.

De facto autocratic rule combined with an absence of de jure democracy is partly due to a leadership culture of “president for life” or access to power by a coup which emerged in these societies and established itself through a “political socialization” process that characterized the post-independence elite rulership generations.

Again, the egoistic style of rulership in pursuit of personal interest and preservation of power has also encouraged the “family-nization” of state powers and institutions in Africa.

Gabon is a good illustration of the genesis and emergence of “love for power” and “family-nization” of politics.

Gabon’s former president, Omar Bongo took power in 1967 upon the death of the country’s first president, Leon Mba. Bongo later dissolved all political parties and established his Parti Démocrtique Gabonais (PDG) as the only political party of the country and the only forum for political dialogue and criticism (Yates, 2005).

From this period until his death in 2009, Bongo, besides being the president, still occupied many ministerial positions.

In response to criticisms in the 1980s for his numerous ministerial occupations in addition to the presidency, Bongo decided to appoint his children and other members of his family to ministries to retain control of these ministries.

While Bongo was running the country with his family, he also did what his counterparts in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Togo did by simply preparing his sons to eventually inherit the presidency upon his death.

In Togo, in February 2005, after the long-serving tyrant ruler, Gnassingbe Eyadema’s death, he was unconstitutionally succeeded by his son Faure Gnassingbe. The people of Togo, as well as the African Union and external powers, protested against this gesture and the disrespect for the state constitution.

Unaccountable political leadership

Leadership in Africa is seriously plagued with issues of corruption and unaccountable governance.

According to a report by the BBC’s Africa Analyst, Elizabeth Blunt in September 2002, corruption in Africa was said to cost the continent nearly $150 billion US Dollars.

Corruption and embezzlement of state resources belong to the worst examples of immoral practices of political societies in Africa and places the continent at the forefront of the world corruption league table.

Thus, bad governance in African countries can also be considered to result from the lack of statesmen in the position of governors.

Corruption and state robbery is endemic in almost all African countries and is a serious flaw in African leadership.

In addition to corruption, kleptocracy and the unjustified amassing of state resources by some irresponsible leaders have stunted development and exacerbated the level of poverty.

Furthermore, embezzlement of state funds accounts for a meaningful proportion of funds that could have helped improve the impoverished state of Africa if properly invested in developmental projects.

In 2009, Transparency International (TI) filed a case against three African presidents for embezzlement.

According to TI these leaders, Omar Bongo of Gabon, Denis Sasou Nguesou of Republic of Congo and Teodore Obiang Nguema of Equatorial Guinea, embezzled millions of euros from their respective countries.

It must be noted that despite the oil produced in Gabon and Equatorial Guinea and with a population of 2 and 1 million, respectively, a vast majority of the people in these countries live in abject poverty.

Weak multicultural political system

The forced unification of diverse ethnic groups and cultures into “nation-states”, an outcome of the colonial arbitrary division of the continent, is one major characteristic of modern African states.

Eboussi (1997) asserts that Africa as a continent has a unique make-up known as “nation of nations” which considers the ethnic groups in each nation as micro-nations.

The diversity in ethnic groups in many of the newly independent states has resulted in the creation of parties along ethnic lines.

Ethnic division in Africa laid the foundation for tribalist-politics which, in turn, encouraged clienteles and neo-patrimonial politics. The result is a political setting that opposes democratic states and hampers their respective transitions to become successful and functional democracies (Bayart, 1993).

Democracy’s characteristic value on equality and rule of law poses a threat to the advantaged and privileged power holders and their political clients in ethnically divided societies in Africa.

Due to fear of losing power, rulers rely on division resulting from the ethnic plurality as a mechanism for consolidating their stay in power in a neo-patrimonial order (Acemoglu et al., 2004). Clapham (1985: 57) postulates that “one of the strongest, most alluring, and at the same time most dangerous forms of clienteles, is the mobilization of ethnic identities”.

Ethnic division provides a fertile ground for political mobilization along patron-client networks. Moreover, ethnic division or tribalist-politicking has a disenfranchising effect on democracy “because it deprives voters of the power to hold their politicians truly accountable through common action with other voters across the land” (Lonsdale, 1986: 141).

Contrary to patrimonialism defined by Max Weber (1978) as a system where military and administrative personnel owe their positions of responsibility to the ruler, neo-patrimonialism in Africa combines elements of patrimonialism and rational bureaucratic rule (Clapham, 1985; Bratton et al., 1997; Erdmann, 2002).

Unlike in patrimonial systems where there is one patron, the ruler, neo-patrimonialism revolves more around the arrangement of services and resources between clients and political patrons.

Exchanges in neo-patrimonialism involve the transfer of public resources (money, ministerial positions, and contracts) by the political patrons as a reward for loyalty or support from the people (Weber, 1978).

Clientelism, another side of neo-patrimonial rule, is the exchange of services or state resources for political support from ethnic-based politicians serving as clients to the ruling patron.

Thus, in most countries, where the transition processes of the second liberation is stalled, there still exists the challenge of breaking down this clienteles network in favor of de facto democratic institutions.

In sum, the current research in its bid to aid with the proper understanding and appreciation of the impact and effects of the current African leadership approach and contemporary leadership approaches (transformational) on sustainable development provides the LIE conceptual framework that shows two main leadership styles; one built on a desire to get a particular job done and make a living while the other is built on man’s need for meaning (Covey, 1992).

FRAMEWORK FOR LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

The Current Situation

- The environment has changed — it is more complex, volatile, and unpredictable.

- The skills needed for leadership have also changed — more complex and adaptive thinking abilities are needed.

- The methods being used to develop leaders have not changed (much).

- The majority of managers are developed from on-the-job experiences, training, and coaching/mentoring; while these are all still important, leaders are no longer developing fast enough or in the right ways to match the new environment.

The Challenge Ahead

- This is no longer just a leadership challenge (what good leadership looks like); it is a development challenge (the process of how to grow “bigger” minds).

- Managers have become experts on the “what” of leadership, but novices in the “how” of their development.

The following session is divided into two sections.

The first (shorter) section focuses on the current environment and the challenge of developing leaders in an increasingly complex and uncertain world.

The second looks in depth at four leadership development trends and the emerging practices that could form the basis of future leadership development programs.

1. More focus on vertical development

There are two different types of development – horizontal and vertical.

A great deal of time has been spent on “horizontal” development (competencies), but very little time on “vertical” development (developmental stages).

The methods for horizontal and vertical development are very different.

Horizontal development can be “transmitted” (from an expert), but vertical development must be earned (for oneself).

2. Transfer of greater developmental ownership to the individual

People develop fastest when they feel responsible for their progress (decentralization).

The current model encourages people to believe that someone else is responsible for their development – human resources, their manager, or trainers.

We will need to help people out of the passenger seat and into the driver’s seat of their development.

3. Greater focus on collective rather than individual leadership

Leadership development has come to the point of being too individually focused and elitist.

There is a transition occurring from the old paradigm in which leadership resided in a person or role, to a new one in which leadership is a collective process that is spread throughout networks of people.

The question will change from, “Who are the leaders?” to “What conditions do we need for leadership to flourish in the network?”

How do we spread leadership capacity throughout the organization and democratize leadership?

4. Much greater focus on innovation in leadership development methods

There are no simple, existing models or programs that will be sufficient to develop the levels of collective leadership required to meet an increasingly complex future.

Instead, an era of rapid innovation will be needed in which organizations experiment with new approaches that combine diverse ideas in new ways and share these with others.

Technology and the web will both provide the infrastructure and drive the change.

Organizations that embrace the changes will do better than those who resist it.

Four Trends for the Future of Leadership Development

The “what” and “how” of leadership development:

Horizontal development

Horizontal and vertical development HR/training companies, own development each person owns development.

Leadership resides in individual managers.

Collective leadership is spread throughout the network.

UNIT 1 – The Challenge of Our Current Situation: The Environment Has Changed

If there were two consistent themes as the greatest challenges for current and future leaders, it was the pace of change and the complexity of the challenges faced.

The last decade has seen many industries enter a period of increasingly rapid change. The most recent global recession, which began in December 2007, has contributed to an environment that is fundamentally different from that of 20 years ago.

Roland Smith described the new environment as one of perpetual white water. His notion of increased turbulence is backed up by an IBM study of over 1,500 CEOs.

These CEOs identified their number one concern as the growing complexity of their environments, with the majority of those CEOs saying that their organizations are not equipped to cope with this complexity.

- Volatile: Change happens rapidly and on a large scale.

- Uncertain: The future cannot be predicted with any precision.

- Complex: Challenges are complicated by many factors and there are few single causes or solutions.

- Ambiguous: There is little clarity on what events mean and what effect they may have.

In the literature, researchers have identified several criteria that make complex environments especially difficult to manage.

- They contain a large number of interacting elements.

- Information in the system is highly ambiguous, incomplete, or indecipherable. Interactions among system elements are nonlinear and tightly coupled such that small changes can produce disproportionately large effects.

- Solutions emerge from the dynamics within the system and cannot be imposed from outside with predictable results.

- Hindsight does not lead to foresight since the elements and conditions of the system can be in continual flux.

In addition to the above, the most common factors seen as challenges for future leaders were:

- Information overload.

- The interconnectedness of systems and business communities.

- The dissolving of traditional organizational boundaries.

- New technologies that disrupt old work practices.

- The different values and expectations of new generations entering the workplace.

- Increased globalization leading to the need to lead across cultures In summary, the new environment is typified by an increased level of complexity and interconnectedness.

One example, given is the difficulty that managers were facing when leading teams spread across the globe. Because the global economy has become interconnected, managers felt they could no longer afford to focus solely on events in their local economies; instead, they were constantly forced to adjust their strategies and tactics to events that were happening in different parts of the world.

This challenge was compounded by the fact that these managers were leading team members of different nationalities, with different cultural values, who all operated in vastly different time zones – all of this before addressing the complexity of the task itself.

The Skills Sets Required Have Changed – More Complex Thinkers Are Needed

Reflecting the changes in the environment, the competencies that will be most valuable to the future leader appear to be changing.

The most common skills, abilities, and attributes cited by interviewees were:

- Adaptability;

- Self-awareness;

- Boundary spanning;

- Collaboration;

- Network thinking.

A literature review on the skills needed for future leaders also revealed the following attributes:

- The CEOs in IBM’s 2009 study named the most important skill for the future leader as creativity.

- The 2009/2010 Trends in Executive Development study found many CEOs were concerned that their organizations’ up-and-comers were lacking in areas such as the ability to think strategically and manage change effectively.

- Jeffrey Immelt, General Electric CEO, and chairman states that 21st-century leaders will need to be systems thinkers who are comfortable with ambiguity. These manifest as adaptive competencies such as learning agility, self-awareness, comfort with ambiguity, and strategic thinking. With such changes in the mental demands of future leaders, the question will be: how will we produce these capacities of thinking?

The Methods We Are Using to Develop Leaders Have Not Changed (Much)

Organizations are increasingly reliant on HR departments to build a leadership pipeline of managers capable of leading “creatively” through turbulent times. However, there appears to be a growing belief among managers and senior executives that the leadership programs that they are attending are often insufficient to help them develop their capacities to face the demands of their current role.

Based on the literature, the most common current reported development methods were:

- Training

- Job assignments;

- Action learning;

- Executive coaching;

- Mentoring;

- 360-degree feedback.

While the above methods will remain important, it is important to question whether the application of these methods in their current formats will be sufficient to develop leaders to the levels needed to meet the challenges of the coming decades.

The challenge becomes, if not the methods above, then what?

UNIT 2 – Future Trends for Leadership Development: This Is No Longer Just a Leadership Challenge – It Is a Development Challenge

A large number of researchers think that many methods – such as content-heavy training – that are being used to develop leaders for the 21st century have become dated and redundant.

While these were relatively effective for the needs and challenges of the last century, they are becoming increasingly mismatched against the challenges leaders currently face.

Marshall Goldsmith has commented, “Many of our leadership programs are based on the faulty assumption that if we show people what to do, they can automatically do it.” However, there is a difference between knowing what “good” leadership looks like and being able to do it.

We may be arriving at a point where we face diminishing returns from teaching managers more about leadership when they still have little understanding about what is required for real development to occur.

SUMMARY

Some few days ago, I discussed with a pair of friends who are recent graduates from two prestigious universities.

While discussing how to start a new business, my first friend said that at his school, professors now tell them not to bother writing business plans, as you will never foresee all the important things which will happen once you begin.

Instead, they are taught to adopt the “drunken man stumble,” in which you keep staggering forward in the general direction of your vision, without feeling the need to go anywhere in a straight line.

“That’s interesting,” said my second friend. “At our school they call it the ‘heat-seeking missile’ approach. First you launch in the direction of some potential targets, then you flail around until you lock onto a good one and try to hit it.”

About the Author:

Professor Kelly Kingsley is a professional with several years of progressive work experience sharpened over time through the private, public, international sectors and NGOs. He is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy school of Government. Professor of financial forensics and audit, holder of a PhD in public finance, MBA, MLA, he is a certified d forensic accountant, certified forensic finance investigator. He is currently designated as a representative of Cameroon to the regional advisory commission on financial markets, censure at the Central Bank, Project Fund Coordinator, Director for Finance Operations with the Ministry of Finance. Before these functions, he held the position of Assistant Resident Representative with the United Nations and Program Coordinator (consultant) with the African Development Bank.

Bibliography

EDA Pearson. (2009). Trends in executive development. Retrieved from http://www.executivedevelopment.com/Portals/0/docs/EDA_Trends_09_Survey%20Summar y.pdf

Goffee, R. (2006, March). Why should anyone be led by you?: What it takes to be an authentic leader. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Goldsmith, M., & Reiter M. (2007). What got you here won’t get you there: How successful

people become even more successful. New York: Hyperion.

Hackman, J.R. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

IBM. (2010, May). Capitalizing on complexity: Insights from the Global Chief Executive Officer Study. Retrieved from http://public.dhe.ibm.com/common/ssi/ecm/en/gbe03297usen/GBE03297USEN.PDF

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kerr, S. (2004). Executive ask: How can organizations best prepare people to lead and manage others? Academy of Management Executive, 18(3).

Kenney, M. (2007). From Pablo to Osama: Trafficking and terrorist networks, government bureaucracies, and competitive adaptation.

University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

McCauley, C., & Van Velsor, E. (2004). The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McGonagill, G., & Doerffer, T. (2011, January 10). The leadership implications of the evolving web. Retrieved from http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/cps/rde/xchg/SID-6822B895FCFC3827/bst_engl/hs.xsl/100672_101629.htm

McGuire, C., & Rhodes, G. (2009). Transforming your leadership culture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. McIlvaine, A. (2010). The leadership factor. Retrieved from http://www.hreonline.com/HRE/story.jsp?storyId=330860027. 17/10/2017

Uhl-Bien, M., & Russ, M. (2009). Complexity leadership in bureaucratic forms of organizing: A meso model. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(4), 631-650.

IBM, Capitalizing on Complexity: Insights from the Global Chief Executive Officer Study. Retrieved from http://public.dhe.ibm.com/common/ssi/ecm/en/gbe03297usen/GBE03297USEN.PDF

Perrow, C. (1986). Snowden & Boone, 2007. EDA Pearson, Trends in Executive Development. Retrieved from http://www.executivedevelopment.com/Portals/0/docs/EDA_Trends_09_Survey%20Summar y.pdf

A. McIlvaine, The Leadership Factor. Retrieved from http://www.hreonline.com/HRE/story.jsp?storyId=330860027. 10/10/2017

M. Goldsmith and M. Reiter, What Got You Here Won’t Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful.

(Hyperion, 2007). Interestingly, the strong attachment to the pimping technique by senior surgeons has led to the teaching

mantra, “pimp ‘em till they bleed.”

R. Kegan and L. Lahey. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press. 10 Ibid., p. 23.

For a fuller explanation of Torbert & Harthill Associates’ Action Logics, Personal and Organizational Transformations: Through action inquiry with. Dalmar Fisher, David Rooke and Bill Torbert. EdgeWork Press, Boston MA (2000 ISBN 0-9538184-0-3) McGuire and Rhodes (2009) outline six steps they recommend to develop leadership cultures: The Inside-Out, Role Shifting Experience Phase; The Readiness for Risk and Vulnerability Phase; The Headroom and Widening Engagement Phase; The Innovation Phase; The Structure, Systems, and Business Processes Phase; and The Leadership Transformation Phase. To learn about methodologies for how individuals vertically develop, refer to Kegan and Lahey (2009).

R. Goffee, Why Should Anyone Be Led by You?: What it takes to be an authentic leader (Harvard Business School Press, March 2006).

For more on Kenney’s fascinating study on how drug cartels and terror groups became learning organizations, see his book From

Pablo to Osama: Trafficking and terrorist networks, government bureaucracies, and competitive adaptation (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007).

Executive Ask: How can organizations best prepare people to lead and manage others? (Academy of Management Executive 18(3), 2004)

To learn more, refer to this article by Chelsea Pollen from Google, who outlines the ways in which online social tools can be used for development: http://www.elearnmag.org/subpage.cfm?section=reviews&article=19-1. 12/10/2017

J. R. Hackman, Leading Teams: Setting the stage for great performances. (Harvard Business Press 2002).

G. McGonagill and T. Doerffer, The Leadership Implications of the Evolving Web, (January 10, 2011). Retrieved from http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/cps/rde/xchg/SID-6822B895-FCFC3827/bst_engl/hs.xsl/100672_101629.htm

McGuire and Rhodes, Transforming Your Leadership Culture (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009).